If you’re buying an aircraft, here’s how to structure the prebuy.

Over the past six months, my company’s prebuy activity has gone right through the roof. We’ve been responding to 30 to 50 prebuy requests a month, perhaps four times as many as we were seeing a year ago.

I’m not quite sure what this means for the health of general aviation. On one hand I’m seeing a lot of owners selling their airplanes, but on the other hand I’m seeing a lot of other folks buying them. And on one hand I’m seeing owners selling their airplanes because they can’t afford to keep them and aren’t using them enough, but on the other hand I’m seeing owners selling their airplanes because they’re upgrading from singles to twins or from pistons to turbines. Occasionally, the sellers turn out to be banks trying to get rid of repossessed planes.

It’s a confusing picture, but overall my impression is optimistic.

As manager of prebuys, my company always represents prospective buyers in these transactions. (Often the sellers are represented by brokers, although sometimes they’re do-it-yourselfers.) Having managed more than 500 prebuys in the past few years we’ve pretty much got it down to a science. We’ve also seen pretty much everything that can possibly go wrong and every mistake that can be made.

Who and where

When a prospective buyer finds an airplane he likes and asks us to manage a prebuy on it, the first challenge is to choose a service center or mechanic to examine the aircraft. This is one of the most important decisions that will determine if the prebuy has a good outcome. There are three important rules we follow in making this choice.

First, the prebuy examination* must be done by a shop or mechanic with extensive expertise with the specific aircraft make and model involved. Since the mechanic will have only a limited amount of time to examine the aircraft, it’s essential that he know exactly where to look for problems—i.e., what this model’s most common and serious problems are. This kind of knowledge only comes with extensive experience with the particular make and model. Ideally, the prebuy should be done at a factory authorized service center or type-specific specialty shop.

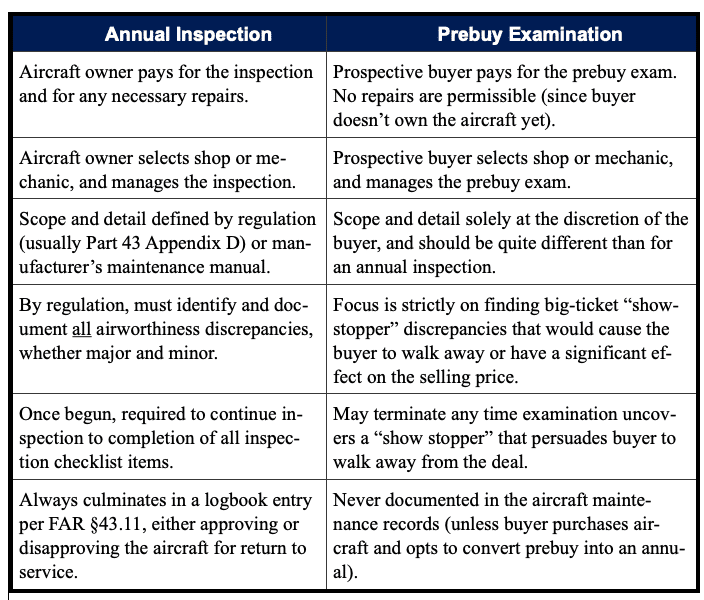

SIDENOTE: * We use the term “prebuy examination” for what many call a “pre-purchase inspection.” We try to avoid using the term “inspection” in connection with a prebuy, because “inspection” has a specific regulatory meaning under the FARs. A prebuy should never be structured as an inspection.

Second, the shop or mechanic chosen to perform the prebuy must have no prior history maintaining the aircraft and no prior relationship with the seller or (if applicable) the seller’s broker. We need the mechanic who performs the prebuy to approach the aircraft with an appropriately skeptical attitude about its condition and airworthiness. A mechanic who has been maintaining the aircraft is naturally going to be predisposed to assume that the aircraft is in good and airworthy condition (particularly if he signed off the last annual inspection). A mechanic who has a relationship with the seller is bound to be reluctant to say anything that might “queer the deal” for his customer or friend. (If the seller or broker recommends a shop or mechanic for the prebuy, that’s probably one you want to avoid using.)

Third, the prebuy needs to be done within a reasonable distance of where the aircraft is located. Few sellers will be comfortable having their aircraft flown halfway across the country for a prebuy, and few buyers want to run up a big fuel bill ferrying an aircraft a long distance when they’re not yet sure they will be buying it. The guideline we use is that the prebuy shop should be within one hour’s flying time from the aircraft’s home base.

Purpose and objectives

Once the prebuy shop has been chosen, the next order of business is providing specific guidance to the mechanic on the desired scope and detail of the examination—in other words, how much time the mechanic should spend examining the aircraft, and on what specific areas and items the examination should focus.

There is nothing in the FARs or maintenance manual that dictates what a prebuy examination should cover. Each individual buyer has to decide how long the prebuy examination should take, how deep it should go, and how much it should cost. Some buyers are content with quick “looksee” that takes only a few hours; others want a full-blown annual inspection. We’ve got some pretty strong opinions about this.

One frequently hears it said “the best prebuy is an annual inspection.” I think this advice is completely wrongheaded. In my view, a prebuy has objectives that are dramatically different from an annual inspection, and should be organized, performed and documented in a very different fashion.

The purpose of an annual inspection (defined by FAR §43.15) is to identify all airworthiness discrepancies, whether trivial discrepancies that cost $50 to correct or major catastrophes that cost $50,000 to resolve. Once started, an annual inspection must continue to completion of all inspection checklist items, and always results in a logbook entry (per FAR §43.11) that declares the aircraft airworthy or unairworthy .

In contrast, the purpose of a prebuy is to provide the prospective buyer the information he needs to (1) decide whether to purchase the aircraft or walk away from the deal, and (2) identify any costly airworthiness issues that he will ask the seller to pay to correct. The prebuy exam should focus strictly on identifying any big “show-stopper” discrepancies that would cost big bucks to fix. It makes no sense to waste time and money looking for minor discrepancies that won’t influence the buyer’s purchase decision or trigger renegotiation of the purchase price.

Unlike an annual inspection, the prebuy will not necessarily go to completion. If some big-ticket show-stopper issue is discovered during the prebuy exam, then an immediate time-out should be called while the buyer considers the implications of the show-stopper, discusses it with the seller, and decides whether to walk away from the deal. Unless and until the show-stopper is resolved between buyer and seller, there’s no point in the buyer spending any additional money on the prebuy exam.

For this reason, the order in which things are examined during the prebuy is important. We always want to start with the most expensive stuff. That typically means the engine and a review of records to identify any non-compliance with Airworthiness Directives and Airworthiness Limitations. Only if that stuff looks okay would we want to proceed to other stuff (airframe, cabin, panel, wheels and brakes, etc.) that require more disassembly and are less likely to reveal show-stoppers. That’s why my company always structures its prebuy checklist in two distinct phases, where phase one covers firewall-forward stuff plus logbook review, and phase two covers everything else.

Also, unlike an annual inspection, the prebuy exam should never result in any logbook entries that document discrepancies or airworthiness determinations. The prebuy is performed at the buyer’s expense, by a shop or mechanic selected by the buyer, and its findings are strictly for the benefit of the buyer to guide his purchase decision and price negotiations.

If the prebuy were to be structured as an “inspection” and the shop finds a significant airworthiness discrepancy, then the buyer is likely to walk away and the seller could find himself over a barrel with a grounded aircraft at a distant and unfamiliar shop that he didn’t choose. That’s hardly fair to the seller, and no seller in his right mind would agree to such an arrangement (although inexperienced sellers often do, often to their detriment).

Scope and detail

Since the goals of a prebuy are so different than those of an annual inspection, the scope and detail should also be very different. In most areas, a prebuy exam need not go nearly as deep as an annual inspection. But in certain areas, the prebuy may need to go deeper.

For example, during a prebuy there’s no reason to jack the airplane and remove the wheels to inspect wheel bearings and micrometer the brake disks, nor is there any reason to measure control cable tensions and control surface deflections. These are all things that have to be done at annual, but none would be likely to influence the buyer’s purchase decision or price negotiations. While they could be airworthiness discrepancies, they’re quick and inexpensive to fix and therefore not worth worrying about in the context of a prebuy.

On the other hand, the condition of the engine’s cam and lifters are a major concern during the prebuy, especially if the aircraft has not flown much recently (a common situation with airplanes that are up for sale). If the aircraft has low- or mid-time engines, a substantial portion of the purchase price is predicated on the presumption that the engine(s) will provide the buyer many years and hundreds of hours of service. A premature engine teardown necessitated by a spalled camshaft or cracked crankcase could be a financial catastrophe for the buyer, and exactly the kind of thing the prebuy exam is intended to prevent.

For that reason, we always spend a good deal of time researching the aircraft logbooks to determine the aircraft’s history of activity and inactivity, where the aircraft was located during any periods of inactivity, and whether the aircraft spent those periods indoors or outdoors. We also borescope the cylinders carefully looking for evidence of corrosion pitting, because if we find pitted cylinders, we get worried about the possibility of a pitted cam. On big-bore Continental engines, we may direct the shop to pull lifters and inspect the cam—something that would never be done during an annual inspection.

On Lycomings, it’s normally impossible to inspect the cam without removing cylinders (which would be inappropriately invasive), so we have to resort to other methods. One strategy we’ve used successfully is such situations is to persuade both seller and buyer to put an agreed-to portion of the purchase price in escrow for a year—if the engine starts “making metal” during the next 12 months, the money goes to the buyer to fund the premature teardown, otherwise it goes to the seller at the end of the 12 months.

Convert prebuy to annual?

Once the prebuy is complete and the prospective buyer has decided to purchase the aircraft and has taken title to it, there’s nothing to prevent the new owner from converting the prebuy into a full annual inspection. In fact, this is often quite a sensible thing to do.

After all, the logbook research has already been performed, the aircraft is already opened up, and much of the airframe, engine and propeller inspection has already been completed. So finishing up the annual inspection, repairing any remaining discrepancies, and completing the logbook entries and other necessary annual inspection paperwork is often the most cost-efficient course of action.

A possible downside can arise when the aircraft’s new home base is a long distance from where the prebuy exam was performed. In this situation, if the new owner converts the prebuy into an annual, then flies the aircraft home and some post-annual problems arise, it’s usually impractical to take the aircraft back to the shop to have those issues addressed. This is worth thinking about when deciding whether or not to convert a prebuy exam into an annual inspection.

Key takeaways

- Have the prebuy exam performed by a shop or mechanic that has lots of experience with the particular make and model.

- Make sure the prebuy shop or mechanic is not one that has maintained the aircraft before, and has no prior relationship with the seller or his broker. This usually means that the aircraft will have to be flown to the prebuy shop, which should be within a reasonable distance of the aircraft’s home base (typically one hour’s flying time or less). If the seller won’t agree to this, walk away.

- The prebuy and any ferrying expenses should be paid for solely by the buyer. Never agree to have the buyer and seller split the costs of the prebuy, because in that case the seller will want to control the location and scope of the prebuy.

- Never structure a prebuy as an “inspection”—particularly not as an “annual inspection.”

- Start with the expensive stuff firewall-forward plus the logbook review. Don’t waste time and money looking for nit-picky stuff that won’t affect the purchase decision or price negotiations. Focus strictly on finding big, expensive “show-stoppers.”

- If you find a big show-stopper, halt the prebuy exam and contact the seller. If the seller agrees to pay to resolve the show-stopper, then resume the exam; if not, cut your losses and walk away.

- Once you’ve bought the aircraft, it sometimes makes sense to convert the prebuy into an annual inspection.

What’s it cost?

While there are a lot of variables, we generally figure a prebuy examination should require roughly:

- 6 hours of labor for a simple fixed-gear piston single like a Cessna 172

- 8 hours of labor for a retractable or advanced-technology normally-aspirated piston single like a Bonanza or Cirrus

- 10 hours of labor for a turbocharged piston single

- 16 hours of labor for a normally-aspirated piston twin

- 20 hours of labor for a turbocharged or pressurized piston twin

As a general rule, that’s about one-third to one-half the cost of an annual inspection.

If a lifter pull and cam inspection is warranted, add about 5 hours per engine.

Also add the cost of the test flight and ferry flights.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: