Jack owns a 2016 Cirrus SR22 with a Garmin Perspective glass cockpit. (The Perspective is basically a G1000 on steroids.) His MFD records tons of data on an SD card—CHTs, EGTs, oil pressure and temperature, MAP, RPM, fuel flow, altitude, TAS, electrical bus voltages and current, even GPS coordinates—and Jack regularly uploads this data to the SavvyAnalysis platform.

Once uploaded, it’s scanned by sophisticated SavvyAI machine-learning algorithms that look for abnormal conditions like failing exhaust valves. Because Jack subscribes to SavvyAnalysis Pro, selected flights are also scrutinized by Savvy’s team of professional data analysts whenever Jack requests this, and he receives a comprehensive report on the health of his engine and the appropriateness of his powerplant management procedures.

Examining the Report Card

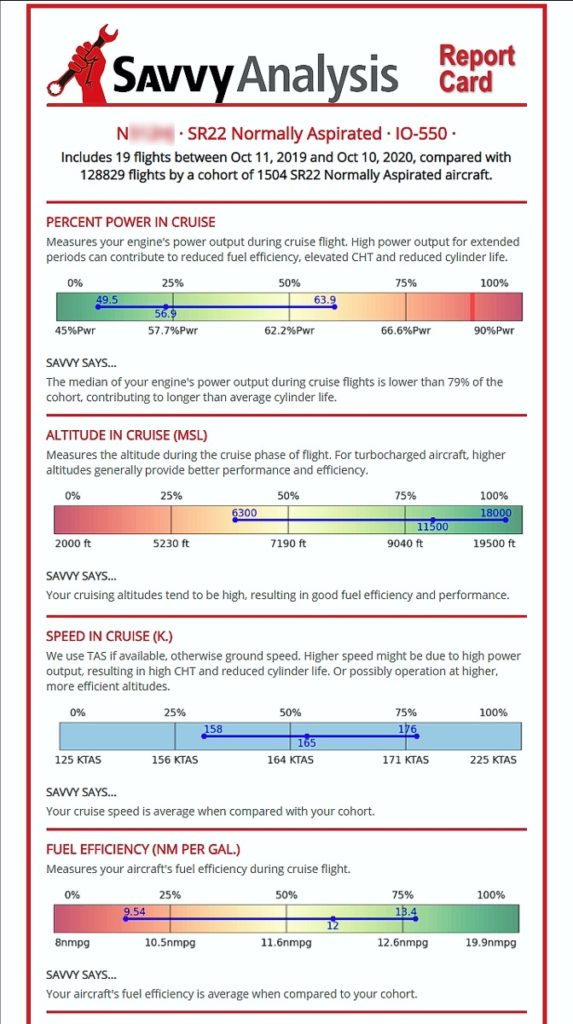

In addition, Jack receives regular “report cards” that graphically shows how his SR22 stacks up when compared to the “cohort” of more than 1,500 other normally aspirated Cirrus SR22s that SavvyAnalysis follows. The report card displays numerous parameters related to performance, efficiency, longevity and health of the aircraft and its engine, and “grades them on the curve” with reference to the cohort.

Jack was reviewing his latest report card. The section focused on the cruise phase of his flights:

Jack thought it looked darn good. It showed that he had been operating at relatively modest cruise power (50%-64%), primarily because he habitually cruised at relatively high altitudes (median 11,500’ MSL, occasionally as high as FL180). These high altitudes allowed him to achieve better than average cruise speeds (158-176 KTAS, median 165 KTAS) and achieve better than average fuel efficiency (9.5 to 13.4 nm/gallon, median 12 nm/gallon). Not too shabby!

Too Hot in the Climb

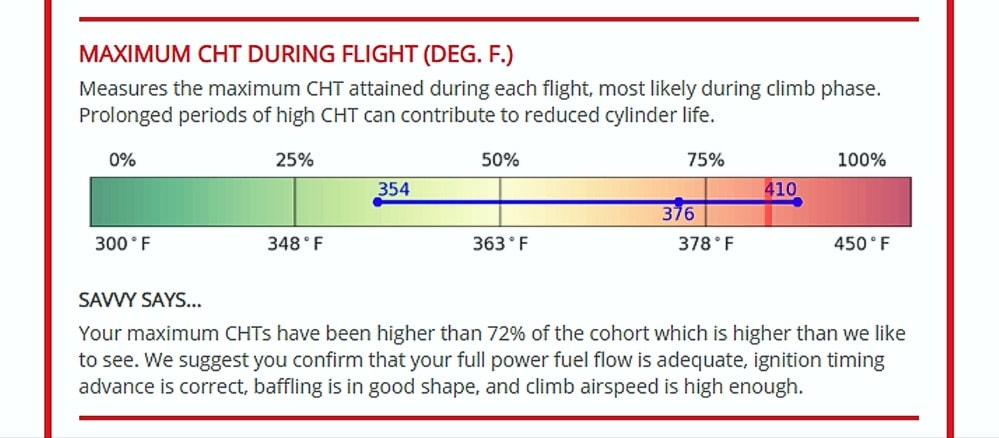

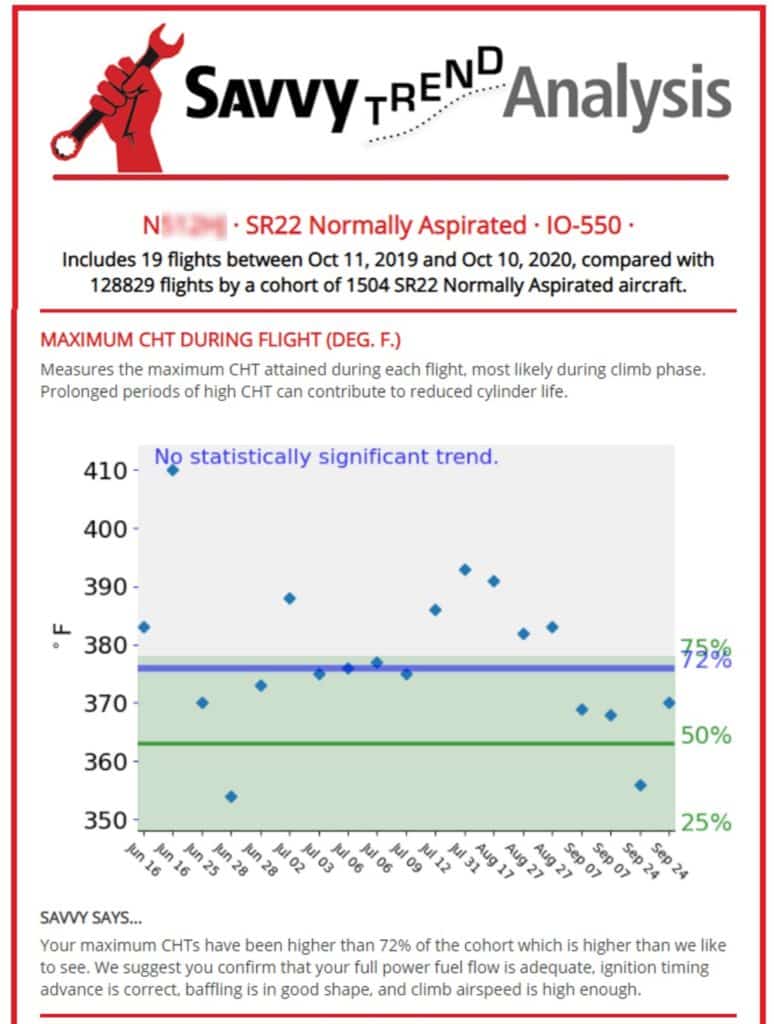

But, as Jack read further down his airplane’s report card, however, he spotted something that got his attention:

The maximum CHT during the climb phase was uncomfortably hot: median 376°F and maximum of 410°F—waaay too hot! (The SR22 has an exceptionally efficient engine cooling system, and it’s unusual to see CHTs above about 360°F in these airplanes.)

This section of the report card said “Your maximum CHTs have been higher than 75% of the cohort, higher than we like to see. We suggest you confirm that your full power fuel flow is adequate, ignition timing advance is correct, baffling is in good shape, and climb airspeed is high enough.”

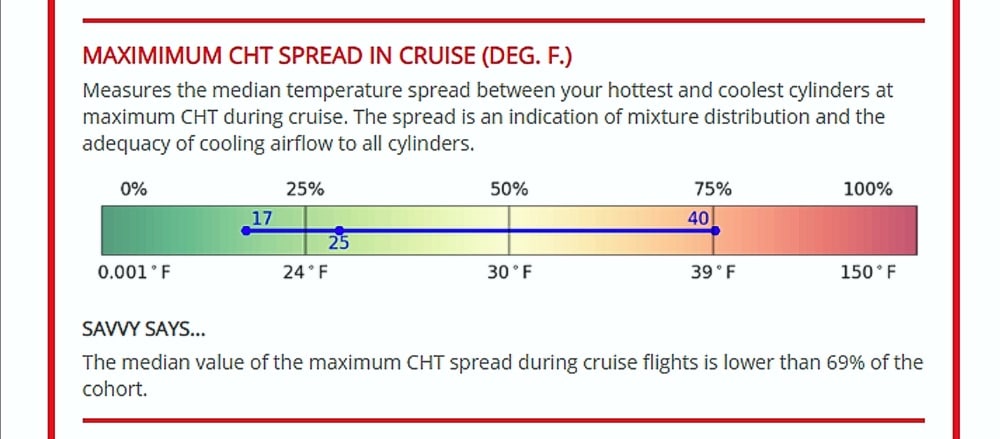

Was this a problem with engine cooling baffles that are missing or mispositioned? While that’s often the cause of high CHTs, the section of the report card that shows maximum CHT spread in cruise…

…makes it clear that Jack’s cooling system is in tip-top shape. The CHT spread measures the difference between the hottest and coolest CHT, and Jack’s spread was exceptionally good, better than 69% of the cohort. So the problem must be something else.

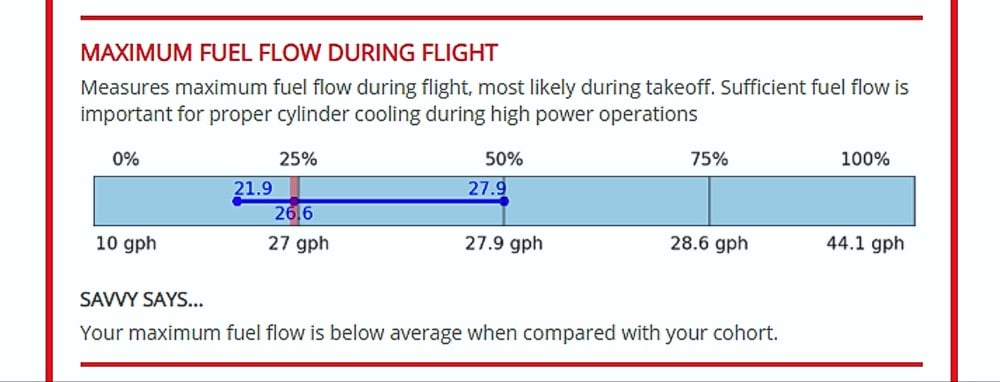

Inadequate Fuel Flow?

Indeed Jack’s report card clearly showed that his maximum fuel flow at takeoff power was less than it ought to be:

Jack’s median takeoff fuel flow was only 26.6 GPH, compared to the cohort average of 27.9 GPH. In other words, Jack’s fuel flow was at least 1.3 GPH too low—and that would make a big difference in engine cooling during climb. (Actually, we’d prefer to see it adjusted to at least 28 GPH.)

What did happen?

Jack hadn’t really noticed these high CHTs in climb, and he wondered how long this had been going on. To find out, he turned to his airplane’s trend analysis, yet another very useful report available to SavvyAnalysis Pro subscribers:

The trend report showed that the high climb CHTs had been a problem for quite some time. The highest recorded CHT of (gasp) 410°F took place in mid-June, and all the flights from mid-July to late August had CHTs that were uncomfortably hot. Starting in September, the CHTs came down quite sharply—most likely correlated with the onset of cooler weather.

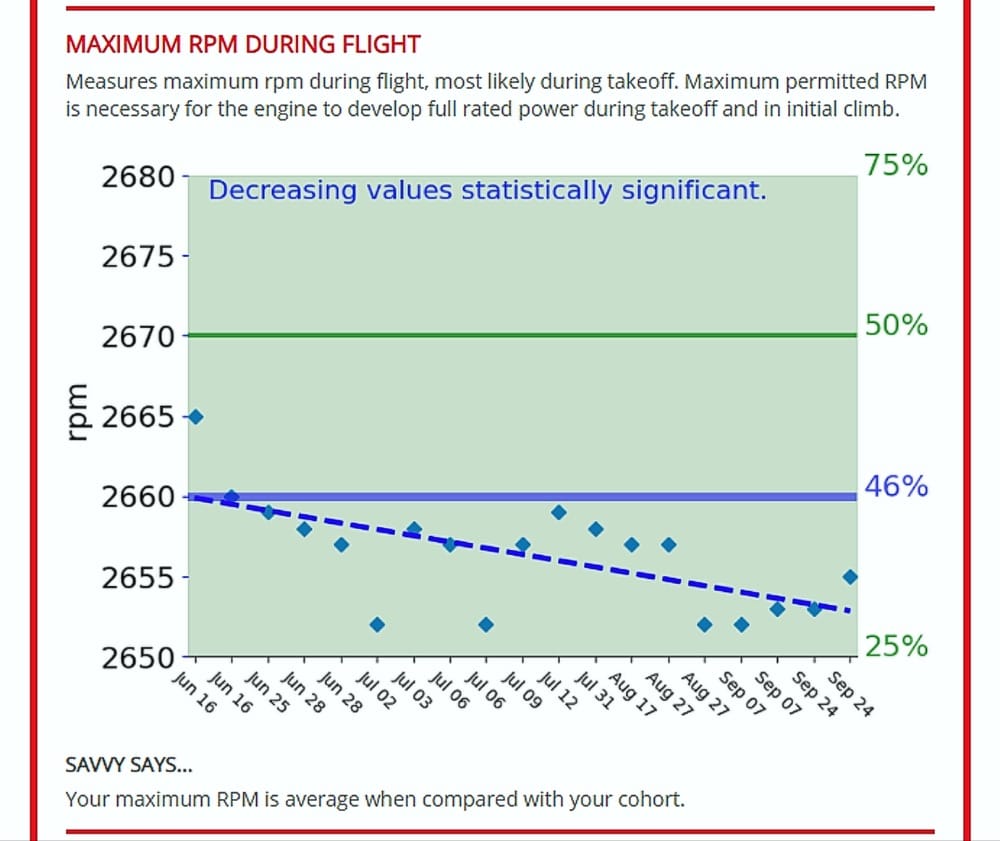

While looking at the trend report, another thing caught Jack’s eye:

This shows that takeoff RPM for Jack’s airplane had been creeping lower over time in a statistically significant way. Maximum rated takeoff power on Jack’s Continental IO-550-N engine requires 2,700 RPM. Most mechanics adjust the prop governor slightly lower than this to avoid spurious overspeed alerts from the Garmin MFD during takeoff. Ideally, the governor should be adjusted to 2,675-2,680 RPM. However, Jack’s takeoff RPM was around 2,660 in mid-June and drifted down to nearly 2,650 by mid-September.

Jack made a note to have his shop adjust the prop governor at the next oil change.

Subscribers to SavvyAnalysis who fly any of the hundreds of aircraft makes and models for which we have a cohort automatically receive report cards and trend analysis reports on a regular basis, and can also retrieve them on-demand at any time. These reports can be incredibly useful in identifying mechanical and operational issues and spotting significant trends.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: