Last week I heard an oldie but goodie. A couple of veteran pilots were talking to a new pilot about flying single engine planes over rough terrain at night. One of the high-timers said “If the engine quits, you pick a spot, turn on the landing light and if you don’t like what you see you turn it off again.” We all know the risks of flying, and the stats say that recurrent training and good maintenance help mitigate those risks. If we were – as the ad says, “stupid rich” – we’d have a team of mechanics check the airplane after every flight, like a Formula 1 team, and pronounce it ready for the next flight. The next best thing is to look at the engine data.

Usually in a puzzler we use an example where the data identified a problem and suggested a remedy. We’ll get to that, but before we do I want to spend a little time on questions we can’t answer, or won’t answer. Even if the team of mechanics performed their post-flight inspection and gave a thumbs-up, we’d still perform a thorough pre-flight inspection before yelling “Clear prop!” FAR 91.013 says we have to, plus it’s smart. FAR 91.7 (b) adds “The pilot in command of a civil aircraft is responsible for determining whether that aircraft is in condition for safe flight.” Sometimes, pilots ask for our help in making that determination. We get questions like “Would you be concerned?” “Do you think it’s safe to fly?” or “Do you think I can put this off until the next annual?”

When Savvy Analysis Pro was born, we made two decisions. One was that it would be a web-based service, not a phone-based service, because we needed a contemporaneous record of any advice we give, and we wanted to be able to offer the service for a reasonable price. Once in a while we have a client that insists on a phone chat, and we politely decline for those reasons. The other decision was we would provide analysis and recommendations for engine longevity, but in the end the question of safety of flight and airworthiness was going to be determined by the owner or the FAA-certified A&P/IA.

Beyond the Scope

Answering “Do you think it’s safe to fly?” is beyond the scope of the service we can reasonably provide, but here are two scenarios where analysis can help you make that decision. If we see a CHT that has been operating normally instantly jump to 500º F. and hug the high limit – never moving – and the EGT for that cylinder remains normal, and the other cylinders are normal, the probability is that the CHT probe has failed and the cylinder is operating normally. We’re not going to pronounce it “safe to fly” – that’s your call to make – but hopefully our ability to differentiate real data from bogus data helps you make that decision.

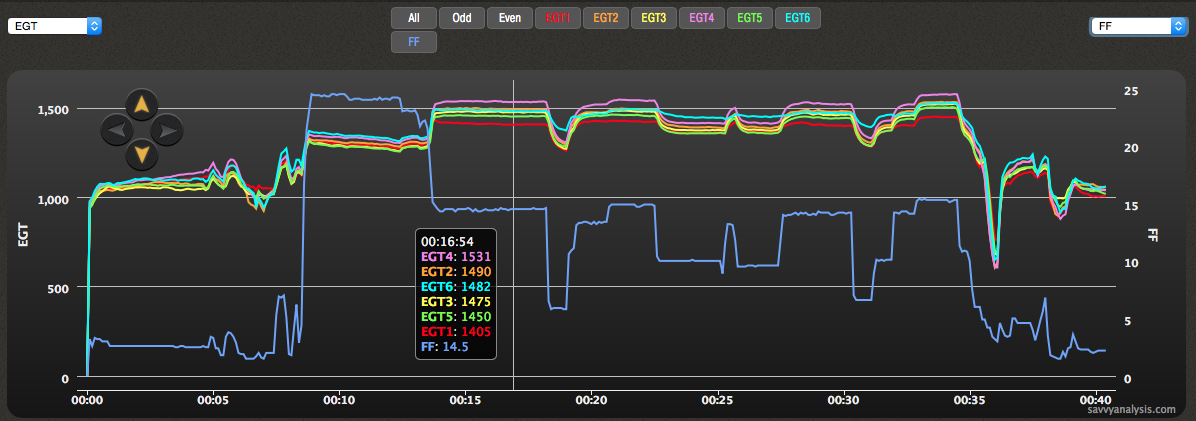

One of the key words in this scenario is instantly, because real CHTs don’t change instantly. The screenshot above is CHT data from a Cardinal with a Lycoming IO-360. FF is reduced and CHT 2 starts a dramatic – but not instant – climb to the danger zone. The trace shows a significant drop when the event is over, but our sample rate here is 6 seconds, so about 2 minutes elapse while the cool down takes place. Another scenario where analysis can help you decide safety of flight is when we see something troubling that merits further investigation. When we see what appears to be a pre-ignition event, and the data seems reliable, we recommend a borescope inspection of that cylinder before further flight.

The landing light joke came to mind this week when I encountered two LOP mag checks with FF changes during the check. The pilots set the FF on both mags, switched to one mag, didn’t like the roughness they felt, and increased FF until it went away. The goal of the LOP mag check – aka ignition stress test – is to identify weaknesses in the ignition system. The stress is the lean mixture, because a leaner mixture is harder to ignite, and misfires or flameouts that appear under stress will be masked by a richer mixture. Changing FF during the LOP mag check also means we can’t draw conclusions about mag timing by comparing changes in EGT.

Pinched baffle seals

As promised, here’s our puzzler for the month – data from a Malibu Matrix with a Lycoming TIO-540.

CHT 3 showed an abnormal pattern so I isolated that trace on bottom, and altitude on on top. Why altitude? Trust me on this – if I put fuel flow, RPM, manifold pressure, oil temp or pressure, you wouldn’t see a correlation. With altitude, every time you see a major change in altitude, the CHT pattern changes a little. The first step in analysis is to determine the reliability of the data. The second step is to spot the abnormality. The third step is to see what else is changing that might be causing the abnormality.

In this case we’re using altitude as a proxy for airspeed and angle of attack. So what’s happening? When the airplane levels off and speed increases, the airflow inside the engine compartment changes. Engine baffles can be metal – the inter-cylinder baffles in the gaps between cylinder heads – or they can be the orange or black silicone strips that seal the cowls. Since this oscillation in CHT does not have a correlation in the combustion family (FF, MAP, RPM), it appears to be cooling-related and looks like something loose enough to change its wobble with changes in the engine compartment.

Also of note is that there is no oscillation in either cyl 1 or cyl 5 – both neighbors of 3 – which we might see if it were the metal baffle instead of the baffle seal. Experience with 6-cylinder engines tells us that the seals around 3 and 4 can be problematic, because the long strip gets pushed from both ends and sometimes flexes in the middle. Because we’re not sure, we’d recommend checking all baffles around cylinder 3, but the pattern points to the seal.

A few years ago I taxied to the runup area and noticed that my engine data monitor hadn’t powered up, even though the avionics bus and other radios were on. For a moment, I calculated the risk of flying without it. After all, I knew the MAP and prop settings that should give me safe CHTs in climb out, and the mixture setting for LOP cruise for the altitude I had chosen. Not my first rodeo. “Should I be concerned?” It was day VFR, and a relatively short flight – not the first leg to AirVenture. Still, I had decided to taxi back to the hangar to investigate, but I decided I should gather more information and power the avionics bus down and power back up. I informed ground control and did that, and the data monitor came online. The breaker hadn’t popped, the risk had been analyzed and calculated, so I decided to complete the flight. Then, of course – as we tend to do with an anomaly – I stared at it, wondering when it would quit again. Eventually I stopped staring, and it has never done that again. So far…