If your aircraft isn’t airworthy but you need to fly it anyway, here’s how.

As every pilot knows, it’s strictly against the rules to fly an unairworthy aircraft:

§91.7 Civil aircraft airworthiness.

(a) No person may operate a civil aircraft unless it is in an airworthy condition.

(b) The pilot in command of a civil aircraft is responsible for determining whether that aircraft is in condition for safe flight. The pilot in command shall discontinue the flight when unairworthy mechanical, electrical, or structural conditions occur.

Now that sounds fine in theory, but sometimes it doesn’t work out so well in practice.

Recently, for example, one of my clients managed to decapitate a runway light with his propeller at an airport in Florida that didn’t have any maintenance services on the field. We were able to get an A&P to drive to the decapitation site in a pickup truck and hang a loaner prop on the airplane, but we then needed to fly back to the shop to have the engine removed for a proper post-prop-strike teardown inspection.

Another client inadvertently let his airplane “go out of annual” while the airplane was tied down at an airport in southern New Jersey. There was a maintenance shop on the field, but after talking to the shop’s Director of Maintenance the aircraft owner concluded that he really didn’t care to have his annual done there and wanted to fly it back to his regular shop for the inspection.

Yet another client in Missouri was in the midst of an annual inspection when he and the IA got into a debate about whether or not several cylinders needed to be removed due to low compression. Ultimately, the aircraft owner decided he wanted to fly the airplane to a different shop at a different airport for a second opinion before authorizing any cylinder removal.

Frequently we run into situations where it’s necessary to have an out-of-annual aircraft flown to a shop for a pre-buy examination. I recall at least one where an out-of-annual aircraft needed to be flown out of harm’s way before the arrival of a big hurricane.

So despite the prohibitions of FAR 91.7, it’s often necessary to fly an aircraft that’s not airworthy. To do that legally, we need to obtain special permission from the FAA in the form of a “special flight permit” (or colloquially, a “ferry permit”).

How to get one

Obtaining a ferry permit is nothing to be afraid of. It’s usually quick and easy. There are basically three steps…

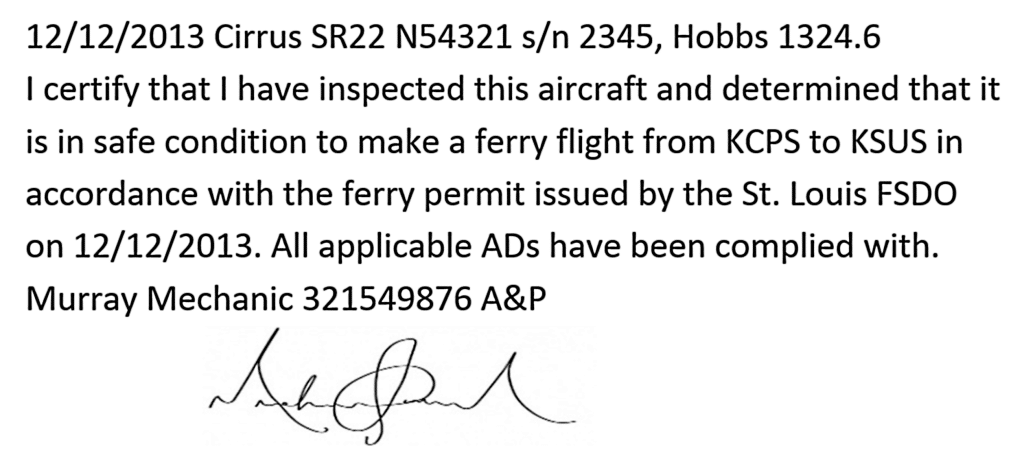

First, you need to find an A&P mechanic who is willing to give you a logbook entry certifying that the airplane is in a safe condition to make the proposed ferry flight. Here’s an example of such a logbook entry.

Note that “safe to ferry” is a very low standard. You’re not asking the A&P to certify that the aircraft is airworthy—only that it’s safe to make just one more flight, and usually a relatively short one. Obviously the aircraft isn’t airworthy; if it was, you wouldn’t need a ferry permit to fly it.

Getting this safe-to-ferry logbook entry from an A&P isn’t an absolute requirement, but without it an FAA Airworthiness Safety Inspector (ASI) from the FSDO will need to come out and inspect your aircraft. Trust me, you don’t want that…and neither does the ASI. So do yourself a favor and get a safe-to-ferry logbook entry (or at least a promise of one from an A&P) before you ask the FAA for the permit.

Things can get a bit more complicated (and costly) if you can’t find a local A&P willing to sign off the safe-to-ferry logbook entry. In that case, you may need to find a mechanic willing to drive or fly to where the airplane is located and inspect it to the extent necessary for him to certify it as safe to make the ferry flight. If you have a regular mechanic who knows the aircraft well and trusts you, he might be willing to sign the entry without actually inspecting the aircraft, but he really isn’t supposed to do that.

Another complication occurs if the ferry flight will traverse non-US airspace. A US ferry permit is valid only in US airspace. Once of my clients needed to ferry an unairworthy Cessna 310 from Toronto to Ohio for major structural repairs; we had to secure two ferry permits, one from Transport Canada and one from the FAA. But even that wasn’t very difficult.

Filling out the application

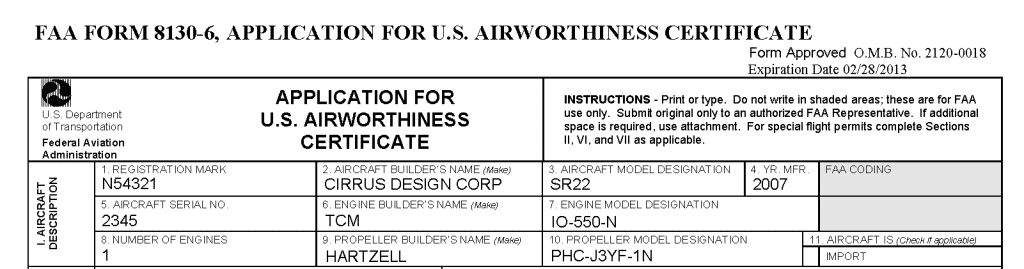

Next, you need to fill out an application form, FAA Form 8130-6 (“Application for U.S. Airworthiness Certificate”), which you can obtain as a PDF fill-in form by going online to http://www.faa.gov/forms and typing “8130-6” into the search box. Don’t be misled by the title of the form—it’s the correct one to apply for a ferry permit.

This two-page form has eight sections (quaintly labelled I through VIII) and is a little intimidating. But for a ferry permit you only fill out sections I, II, and VII and leave everything else blank. In Section I you identify the aircraft, engine and propeller:

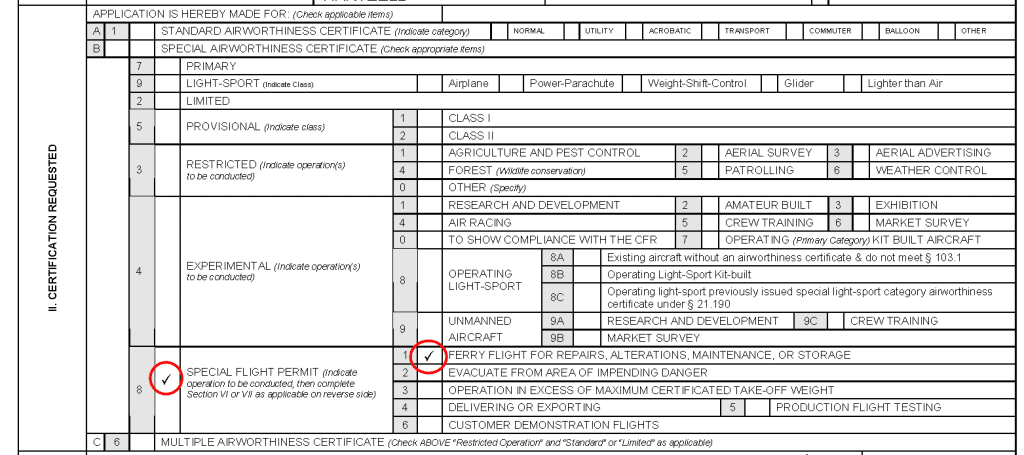

In Section II, you simply check two boxes to indicate that you’re applying for a special flight permit for a maintenance ferry flight:

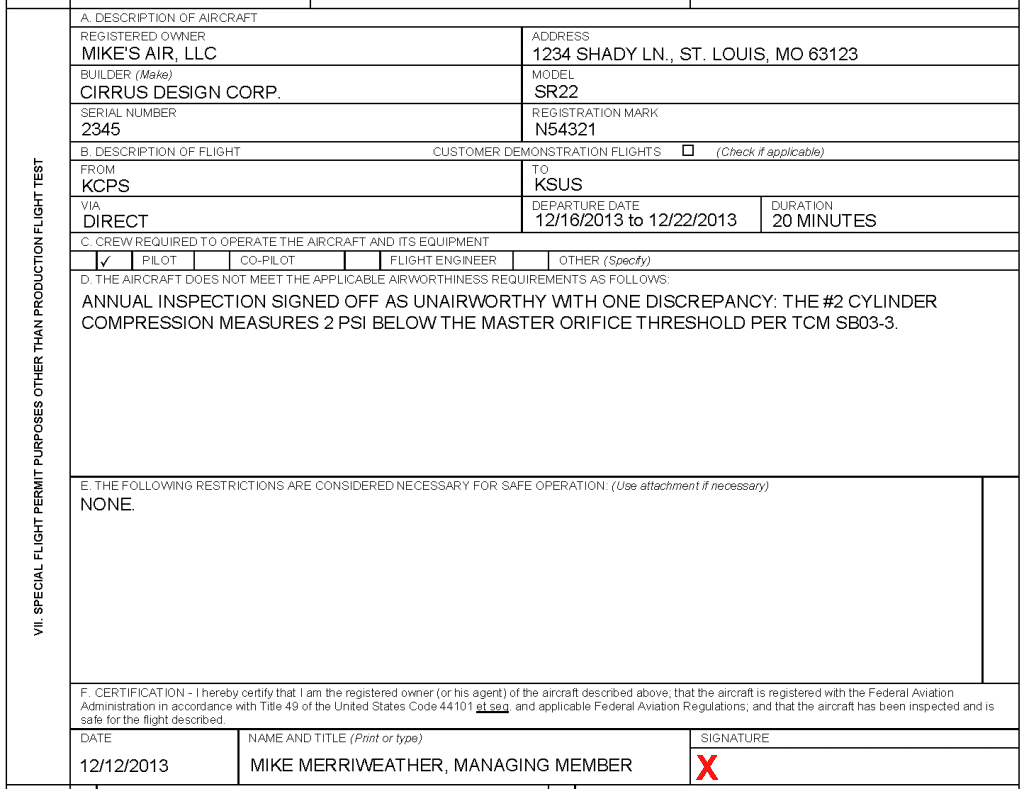

Finally, in Section VII, you state who owns the aircraft, describe the proposed ferry flight, and explain why the aircraft is not airworthy:

At the bottom of Section VII, you sign and date the application.

Submitting the application

Finally, you need to email or fax the completed Form 8130-6 application form to the FAA Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) whose jurisdiction includes the airport where your aircraft is located. If you don’t know which FSDO to contact, ask the A&P who gave you the safe-to-ferry logbook entry, or look it up online at http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/field_offices/fsdo.

Although it’s not necessary to include a copy of the safe-to-ferry logbook entry with your application, I recommend doing so because it will help reassure the FSDO that your request for a ferry permit is reasonable.

Follow up your email or fax with a phone call to the FSDO and ask to speak to the ASI to whom your ferry permit application has been assigned. (If nobody has looked at it yet, your phone call may push it to the top of the list.) The ASI might have a few questions, but unless something in your application or the safe-to-fly logbook entry looks fishy or risky, the ASI will usually fax you back the ferry permit the same day you apply.

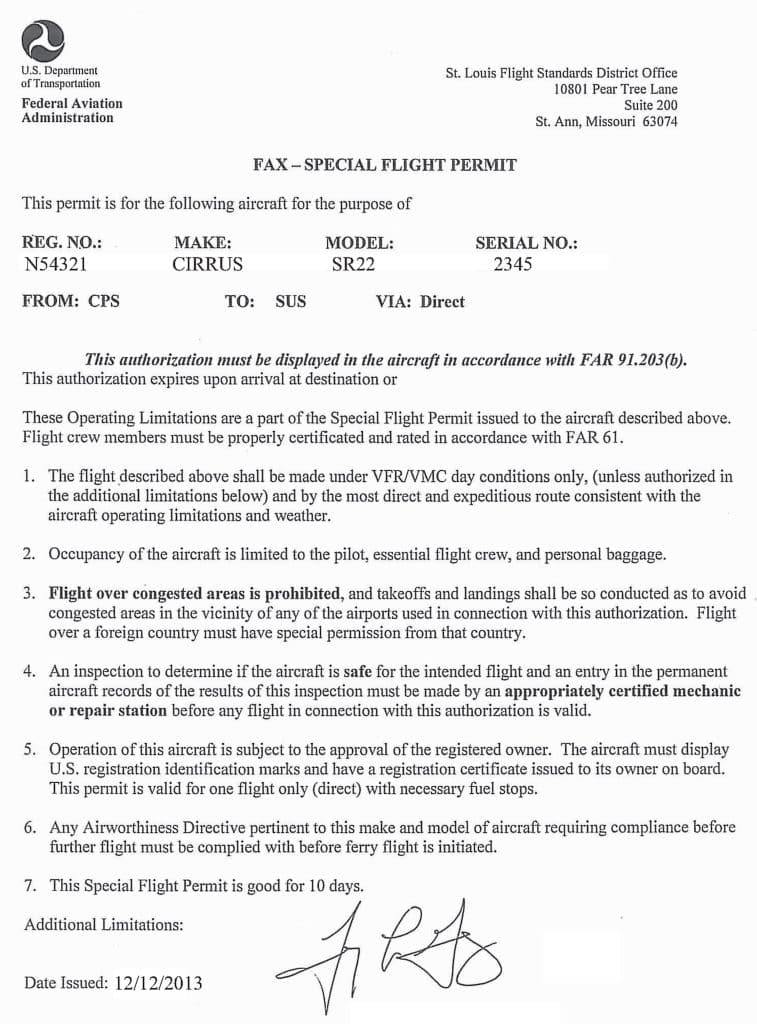

Figure 5 shows what your faxed ferry permit will probably look like.

Making the ferry flight

Normally, the faxed ferry permit will be valid for a 10-day period, giving you some flexibility as to when to make the flight. That’s important, because typically the ferry permit will restrict the flight to being made in day VMC conditions with only essential flight crew aboard (which for most of us means one pilot only).

You must carry the ferry permit aboard the aircraft during the ferry flight, and display it in lieu of the standard airworthiness certificate. It’s also a good idea to carry a photocopy of the signed safe-to-ferry logbook entry, since the ferry permit isn’t valid without that entry. Remember that the ferry permit is valid only for the one proposed ferry flight and expires when you land at the destination.

One more important thing: Do not make the ferry flight without first calling your aircraft insurance agent and making sure that you have coverage for the flight. Many policies will not provide coverage if the aircraft is unairworthy (which it obviously is if you need a ferry permit), but almost all underwriters will provide coverage for the ferry flight at no additional premium if you ask for it before you make the flight.