Under the FARs, an annual inspection is a pass-fail test. Sometimes failing is the best course of action.

Of the nearly 200 rules in Part 91 of the Federal Aviation Regulations, far and away the most expensive for most aircraft owners is this one:

§ 91.409 Inspections. (a) …No person may operate an aircraft unless, within the preceding 12 calendar months, it has had—(1) an annual inspection in accordance with part 43 of this chapter and has been approved for return to service by a person authorized by §43.7 of this chapter…

This means that once a year, we have to turn our aircraft over to an eagle-eyed A&P/IA or FAA-certified repair station and pay them to perform an annual inspection. We then have to pay the shop or mechanic to repair all the airworthiness discrepancies that they find and to comply with all applicable airworthiness directives, airworthiness limitations, and other regulatory airworthiness requirements. The ultimate object of this costly exercise is to obtain a logbook entry containing the cherished magic words that permit us to fly the airplane for another 12 calendar months:

I certify that this aircraft has been inspected in accordance with an annual inspection and was determined to be in airworthy condition. /signed/ Eagle I. Inspector 123456789 A&P/IA

Although that’s the way it usually works, there’s actually another possibility: flunking the annual.

Under the FARs, an annual inspection is actually a pass/fail exam with two possible outcomes. The most common outcome is that the aircraft is found to meet all applicable airworthiness requirements, and we get a logbook entry containing the magic words mentioned above and approving the aircraft for return to service.

How to flunk an annual

However, the regs allow for another possibility: disapproval for return to service. In this case, we receive a logbook entry with a different set of magic words:

I certify that this aircraft has been inspected in accordance with an annual inspection and a list of discrepancies and unairworthy items dated mm/dd/yyyy has been provided for the aircraft owner or operator. /signed/ Eagle I. Inspector 123456789 A&P/IA

Along with such a logbook entry, the inspecting IA will provide us with a separate sheet of paper, signed and dated, listing the discrepancies and/or unairworthy items that the inspector feels must be corrected in order for the aircraft to be airworthy.

This alternative outcome is known as “signing off an annual with discrepancies.” While rare, it can be an extremely useful tool for dealing with unanticipated complications that sometimes arise during an annual inspection. Every aircraft owner should understand how this alternative works and when to consider using it.

Signing off an annual with discrepancies is almost always something that the owner must request. By making such a request, the owner is in essence telling the inspecting IA or repair station:

“Thanks for doing such a thorough job of inspecting my airplane. I’ve decided that I don’t want you to repair one or more of the airworthiness discrepancies you found during the inspection. I’m going to have those discrepancies addressed elsewhere. Therefore, please close up my airplane, give me a list of the uncorrected airworthiness discrepancies, invoice me for the work you’ve performed, and release my aircraft. We’re done.”

A signoff with discrepancies completes the annual inspection. The aircraft does not have to be inspected again for another 12 calendar months. Naturally, the aircraft can’t be flown until the listed discrepancies have been corrected. However, they can be corrected by any shop or mechanic that you wish to use, not necessarily the one that performed the annual inspection. The mechanic who corrects the discrepancies doesn’t even need to be an IA. Once the discrepancies have been corrected (by whomever you chose to do the work), you can fly the aircraft. You don’t need to have the aircraft re-inspected until the next annual inspection comes due.

When to flunk an annual

Why on earth would you ever want to do this? There are a couple of good reasons you might.

One is that you have concluded the shop that performed the inspection isn’t the best qualified shop to make the repairs. For example, perhaps the discrepancy requires extensive sheet metal work or composite repairs, and you and/or your mechanic conclude that it would be advisable to have the work done by a sheet metal or composite repair specialist rather than your regular shop. Same for an issue that you and/or your mechanic feel would be best addressed by an avionics shop. Or perhaps the inspection uncovered a propeller issue and you’d prefer to fly the aircraft to the prop shop rather than have the propeller removed, shipped there and back, and reinstalled. Ditto for an engine issue if you’d prefer to take the plane to an engine shop. Or deicing boots that you’d like to have repaired or replaced by a boot specialist. (I’m a huge believer in using specialists.)

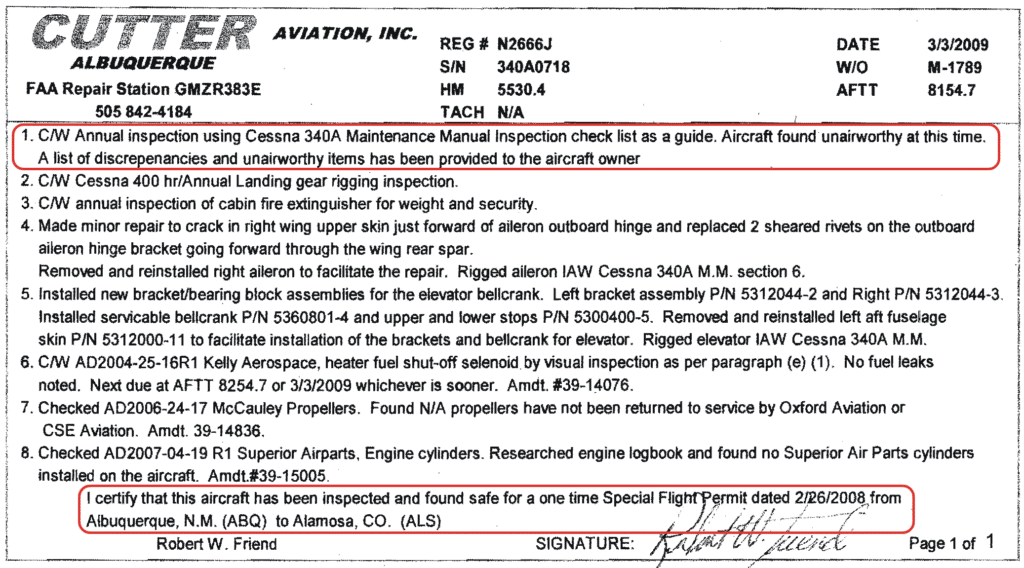

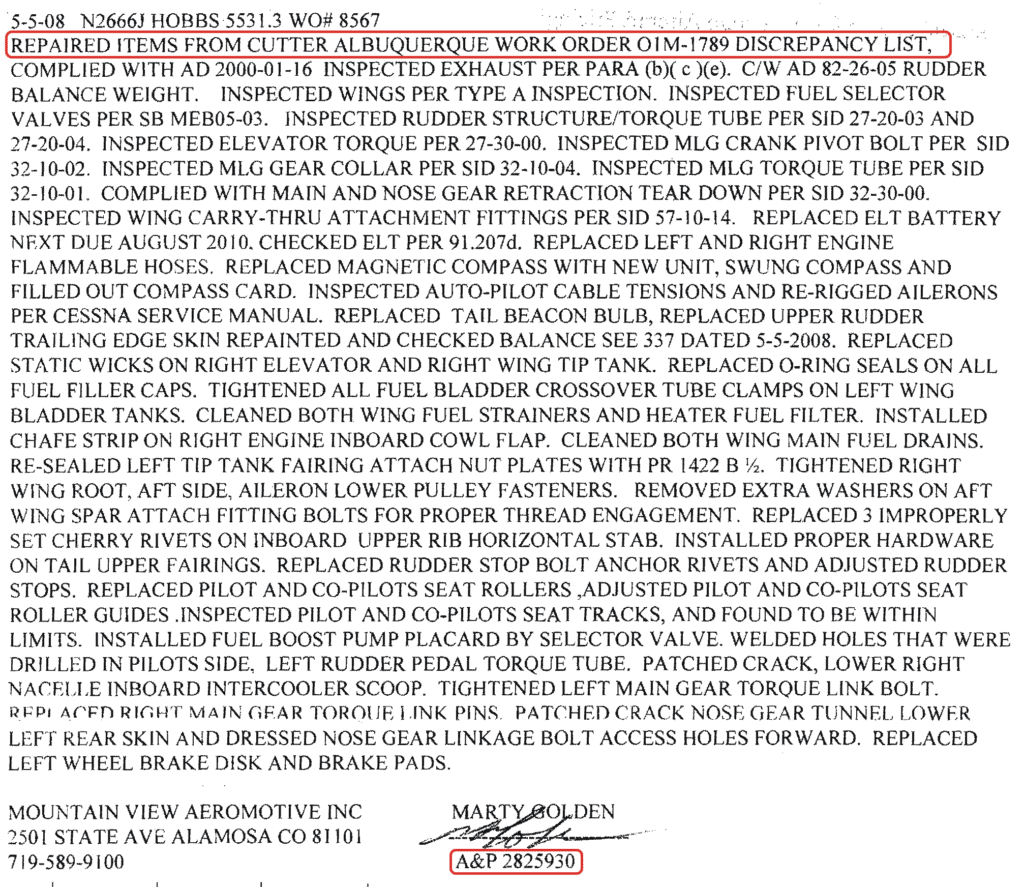

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate just such a situation. The owner of a Cessna 340 had an annual inspection performed by Cutter Aviation in Albuquerque, N.M. Cutter’s inspection apparently uncovered a bunch of airworthiness discrepancies that the owner decided he’d prefer to have addressed by another shop, Mountain View Airmotive in Alamosa, Colo. Consequently, he directed Cutter to do only the minimum work required to put the airplane into ferryable condition (mainly complying with some recurrent ADs), then obtained a ferry permit, flew the airplane to Alamosa, and had Mountain View address all the airworthiness items on Cutter’s discrepancy list.

Note that the Mountain View logbook entry (Figure 2) has an approval signature that states “A&P” and not “IA.” That’s because the mechanic at Mountain View was performing repairs in his capacity as an A&P mechanic, not performing an inspection in his capacity as an IA. Cutter performed the inspection, and no further inspection was required by regulation for another 12 calendar months.

Owner/IA Disagreements

Another reason you might want to flunk an annual is when you find yourself disagreeing with your IA about how to deal with one or more discrepancies.

Suppose, for example, that your engine is 500 hours past TBO. It’s running great, oil consumption is moderate, oil filter is clean, good compressions, oil analysis and borescope results. You see no reason not to keep flying it until there’s some good reason to tear it down. But your IA has a different view: He believes strongly that manufacturer’s TBOs should be respected. “I’ve gone along with your TBO-busting for the past two years, against my better judgment, but 500 hours over TBO exceeds my threshold of pain,” the IA tells you. “I’m just not comfortable signing off this annual unless we overhaul or replace the engine.”

Now, obviously it would have been better if you had this discussion with the IA before you hired him to perform the annual inspection on your airplane. But unfortunately that didn’t happen. Your airplane is in pieces, mid-way through the annual inspection, and now the IA is telling you he’s not willing to approve the aircraft for return to service without $40,000 of engine work that you consider unnecessary and superfluous.

After some discussion, it becomes apparent that you and the IA are deadlocked. You’re not about to spend the $40,000, and he’s not about to sign off your annual unless you do. So how do you resolve the deadlock?

Simple: You direct him to complete the annual inspection without overhauling or replacing the engine, and to sign off the annual with a discrepancy. Once the annual is finished and you get your airplane out of the shop (with a disapproval and a discrepancy list), you go find some other A&P whose views on engine TBOs are compatible with yours and you ask him to clear the discrepancy by certifying that your engine is airworthy. Now you’re good to go.

In the past few years, my firm has managed well over 500 annual inspections. Ninety-nine percent of them went smoothly and concluded with approvals for return to service. But in four cases, we wound up directing the shop to sign off the annual with discrepancies.

In one case, the shop’s chief inspector insisted that both Bendix magnetos had to be replaced (at a cost of more than $2,000) because they were four years old. The chief inspector was convinced that the four-year replacement interval was required by regulation, and we couldn’t persuade him otherwise. Ultimately, we instructed the shop not to replace the mags, had them written up as an uncorrected airworthiness discrepancy, removed the aircraft from the shop, and had another A&P sign off the mags as airworthy. (Shortly thereafter, the stubborn chief inspector was demoted to line mechanic, and ultimately lost his job.)

In another case, the annual of a client’s Cessna 182 uncovered a small windshield crack. We readily agreed that this was an airworthiness item, but the inspecting shop estimated that the windshield replacement would require twice as much labor as we felt was reasonable. We declined the windshield repair, had the windshield written up as a discrepancy, and then had a different shop replace the windshield at much more reasonable cost.

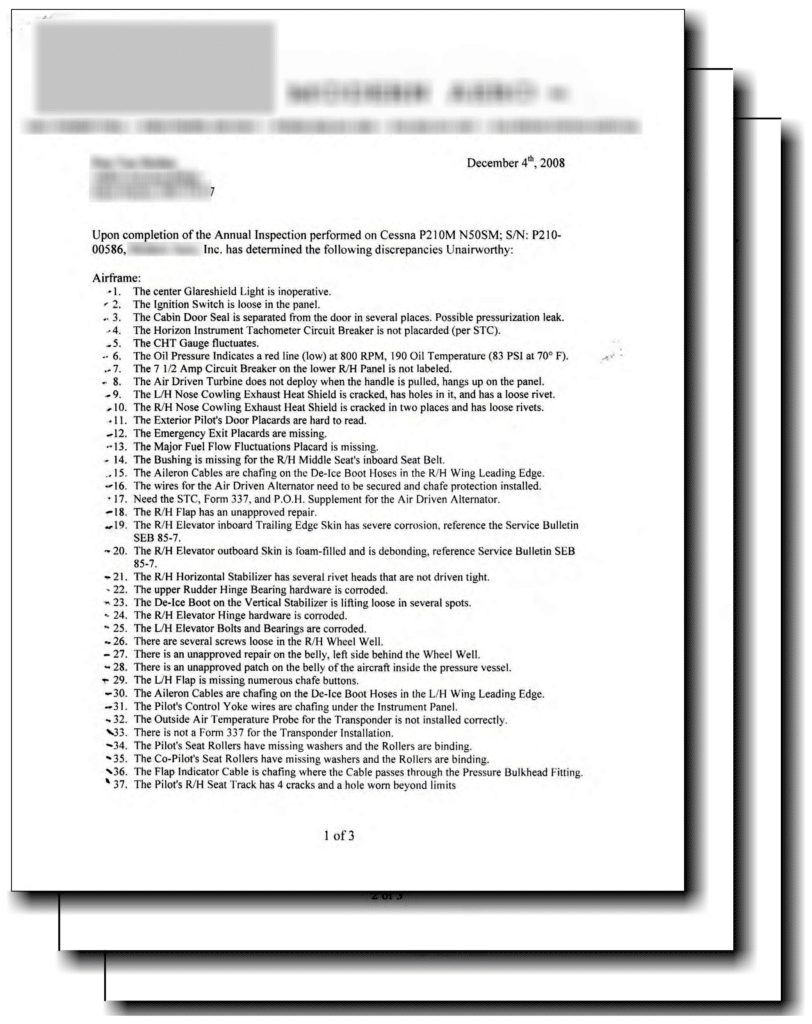

In the third case, the shop that inspected a client’s Cessna P210 estimated that it would cost at least $70,000 to repair the aircraft and sign off the annual as airworthy. After discussing the estimate with the shop’s director of maintenance and finding him to be completely intractable, we directed the shop to cease work, close up the aircraft, and document all the discrepancies they found (three pages worth, see Figure 3) on a massive 43.11 discrepancy list. We then took the aircraft to a different shop, which performed the necessary repairs for less than half what the original shop had quoted.

In the fourth case, the big repair station that inspected a client’s Cirrus SR22 found the screws securing an autopilot servo motor to its bracket were loose, a common problem with these aircraft. We asked them to tighten the screws and apply some Loctite so they wouldn’t loosen again. The shop’s Chief Inspector said he could not tighten the screws without “approved data” and indicated the shop would have to replace the entire servo assembly at the cost of several thousand dollars. After trying to reason with this Chief Inspector without success, we had the shop sign off the annual with a discrepancy on the servo, and had another A&P tighten the screws and clear the discrepancy.

Ferry Permits

If you flunk your annual and receive a disapproval for return to service, you’re theoretically not allowed to fly the airplane until the listed discrepancies are corrected. But sometimes you want or need to move the aircraft to a different airport in order to have those repairs performed. Catch 22?

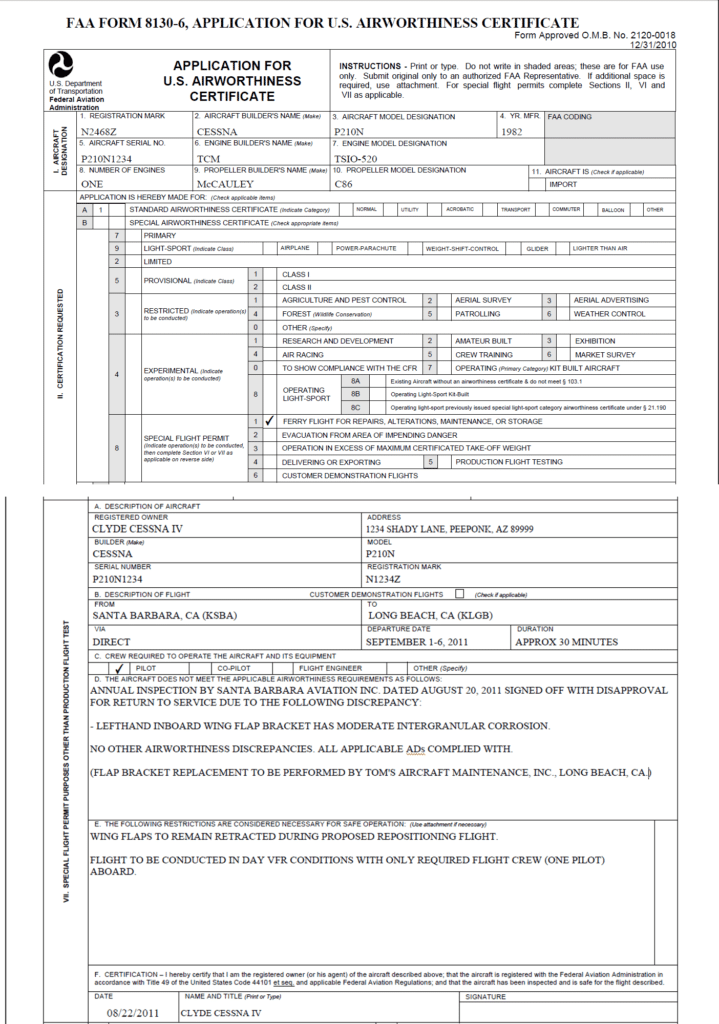

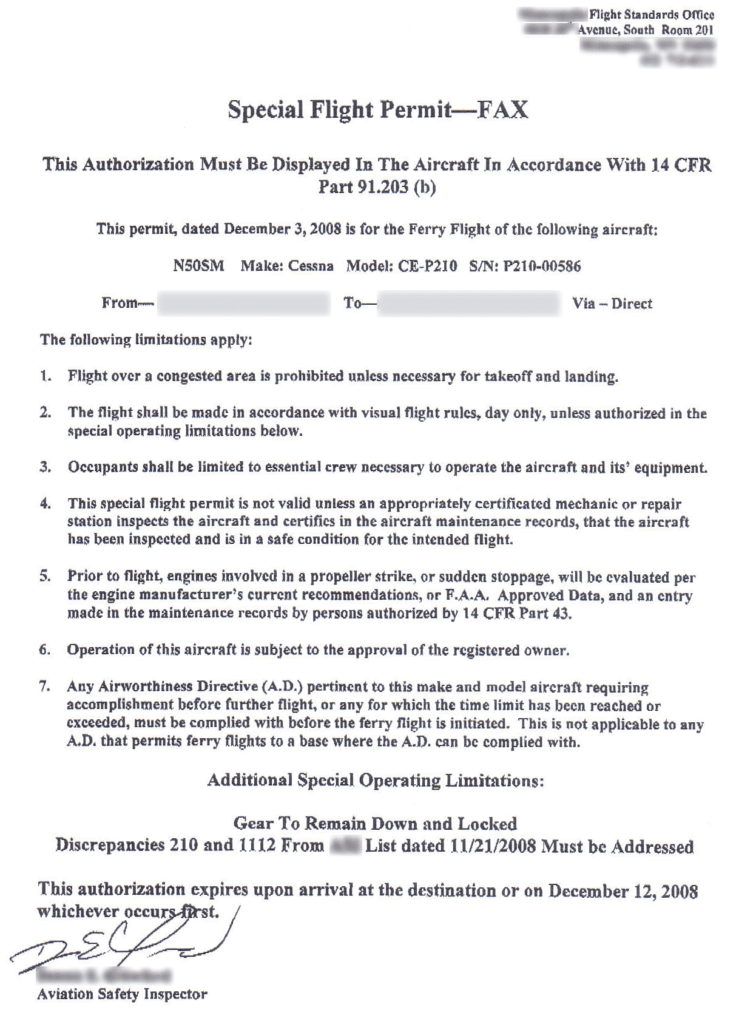

No problemo! That’s why the FAA invented Special Flight Permits (colloquially known as “ferry permits”). A Special Flight Permit is simply special dispensation from the FAA to fly an admittedly unairworthy aircraft from one place to another on a one-time basis, usually in order to reposition it to where repairs are to be performed (or sometimes to evacuate it from impending danger). In most cases, getting a ferry permit is quick and painless.

To get one, you simply need to fill out an FAA Form 8130-6 (“Application for U.S. Airworthiness Certificate” at http://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/form/faa8130-6.pdf). You only need to complete blocks I, II, and VII of the form. See Figure 4 for an example.

You’ll also need a logbook entry from any A&P mechanic certifying that the aircraft is in adequate condition to make the one-time ferry flight safely. The one at the bottom of Figure 1 is a good example of such a logbook entry.

Even if the reason you’re requesting the ferry permit is because you’re deadlocked with an IA over some disputed airworthiness discrepancy, in my experience the IA will be more than happy to provide you with the necessary safe-to-ferry logbook entry. Remember that the IA is just as anxious to get rid of you and your airplane (and get paid for his work) as you are to get your aircraft out of his shop and moved to another shop. Your decision to flunk your annual solves his problem as well as yours, so in all likelihood the IA will be happy to help you obtain your ferry permit and get out of Dodge.

Simply fax your completed Form 8130-6 plus a copy of the A&P’s logbook entry to the local FSDO, and then follow up with a telephone call to the airworthiness inspector on duty at the time. In most cases, the FSDO will fax you back your special flight permit the same day. See Figure 5 for an example. Be sure to carry the permit in the airplane when you make the ferry flight. That’s all there is to it.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: