When things go awry in the sky, litigation isn’t necessarily the best remedy.

My email inbox contained a message with the subject “Legal Question – Advice Needed.” That didn’t surprise me because although I’m not a lawyer, I do regularly participate in aviation litigation—mostly arising from air crashes—as an expert witness and consultant, mainly in cases that involve mechanical or maintenance issues.

The email was from a private pilot who owned a Liberty XL2 that he purchased used nine months earlier. After he flew the aircraft for about 80 hours, the aircraft’s Continental IOF-240-B engine developed a serious engine problem that revealed itself by a low oil pressure indication. The owner’s mechanic ultimately traced the problem to the cluster gear on the rear of the engine’s crankshaft, which was found to be damaged where the starter pinion engaged the cluster gear at each engine start.

“The metal from the damaged gear contaminated the engine and ultimately caused catastrophic damage to the engine,” the owner explained. “I was very lucky that I was not in flight as I was holding short and just seconds from takeoff clearance when I noticed the low oil pressure alarm. The engine still ran and I was able to taxi back to my tiedown and call my mechanic.”

The owner went on to say, “I am considering legal action against Continental for a faulty crankshaft gear, and need some professional advice before proceeding.”

The facts of the case

Further research uncovered a 2014 Continental service bulletin SB14-2 titled “Inspection and Replacement of IO240 Starter and Crankshaft Cluster Gear.” That service bulletin explains that Continental switched to a different kind of lightweight starter assembly manufactured by B&C Specialty Products, and also changed to a redesigned crankshaft cluster gear to accommodate the new starter.

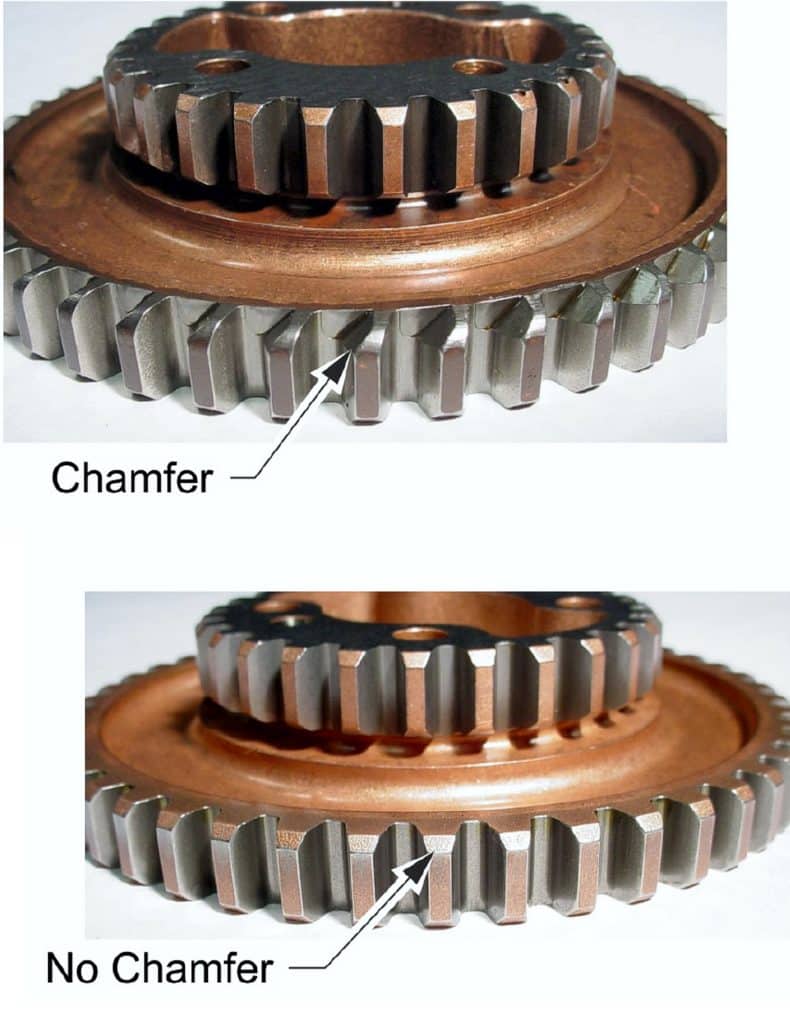

The service bulletin explains that the older starters were “continuous mesh” units whose pinions were continuously meshed with a gear in the cluster gear assembly bolted to the rear of the crankshaft. In contrast, the new B&C starter is an “intermittent mesh” unit that extends its pinion to mesh with the cluster gear when the starter is energized. When the starter is de-engergized, the pinion retracts to disengage the starter from the cluster gear. Use of this new intermittent mesh starter required a redesign of the crankshaft cluster gear. Specifically, the gear teeth were chamfered (beveled) to facilitate reliable meshing of the starter pinion when it is extended.

The service bulletin warns of the peril of using the new intermittent-mesh starter with the older-style non-chamfered cluster gear:

CAUTION: Starters installed using an unmatched or incompatible crankshaft cluster gear may result in a shortened service life, equipment failure, or damage to the engine.

When the service bulletin was issued in 2014, Continental seemed clearly concerned that there might be some IO-240 engines out there using the older-style cluster gear with the new-style starter—perhaps some left the factory in that condition—because the service bulletin calls for removing the starter and inspecting the cluster gear for compatibility and tooth damage “no later than the next scheduled inspection.”

Since that time, the Liberty XL-2 had gone through at least four annual inspections, but this starter removal and gear compatibility check was never performed. Perhaps the inspecting IAs were not aware of SB14-2; the owner told me that his mechanic was unaware of it until the metal showed up in the engine. Or perhaps the inspecting IAs were aware of the service bulletin but chose to ignore it—compliance with service bulletins is not required by regulation for Part 91 aircraft, and consequently IAs are not required to search for applicable service bulletins for such aircraft.

Apparently, Continental did not consider this to be a serious safety-of-flight issue, because it chose to issue SB14-2 as a routine Category 3 service bulletin. Had the company been concerned that someone might fall out of the sky, it surely would have issued it as either a Category 2 Critical Service Bulletin or a Category 1 Mandatory Service Bulletin, and discussed with the FAA the possibility of issuing an Airworthiness Directive mandating compliance. That didn’t happen.

Meantime, the Liberty’s owner had authorized his mechanic to pull the engine and ship it to a reputable engine shop, who reported back that the engine had been seriously damaged by contamination from the damaged cluster gear and that the repair bill might be as much as $25,000. This came as a total shock to this relatively inexperienced aircraft owner, already shaken by the belief that he could have been injured or killed had this problem occurred in flight rather than in the runup area. This engine had accumulated only about one-third of its 2,000-hour TBO, and the owner believed that this fiasco was Continental’s fault and that the company should be made to pay for it.

Some “legal advice”

I’m not an attorney—I don’t even play one on TV—but I did tell the disgruntled Liberty owner that I didn’t think suing Continental over this was a sensible thing for him to do. For one thing, it would seldom make economic sense to sue for damages that are as modest as his appeared to be ($25,000), because the cost of doing so would be prohibitive. Litigation is extremely expensive, usually takes years of expensive legal wrangling, and thus provides a feasible remedy only in cases of wrongful death, serious injury, or large financial loss.

Perhaps the owner could sue Continental in small claims court for up to $10,000 but he’d have to do it without benefit of a lawyer, and he might well have to do it in Mobile, Alabama. Generally, a small claims case must be filed in the state and county where the defendant resides, although there are some exceptions.

More importantly, I told the owner that I had difficulty believing that he had a valid claim against Continental. The company clearly met its “duty to warn” by issuing SB14-2, and would argue that the current and previous owners of the Liberty XL-2 knew or should have known that failure to perform the cluster gear compatibility inspection could result in precisely the kind of engine damage that the current owner was now facing.

“If you have a valid beef with anyone,” I told the owner, “it should probably be with the IAs who repeatedly performed annual inspections on the airplane without performing the inspection called for by Continental. The ignorance of SB14-2 by these IAs is hardly Continental’s fault.” I hastened to point out, however, that the IAs did not have any regulatory obligation to comply with SB 14-2 or any other service bulletin, since this was a Part 91 aircraft. There was never any Airworthiness Directive mandating compliance with SB14-2 because the FAA did not determine that the cluster gear incompatibility represented an unsafe condition that was likely to get anyone hurt or killed.

“Plus, I’m guessing you’re probably not really interested in suing your mechanic,” I added. “You probably want him to continue working on your airplane, and anyway he’s probably not a high-net-worth individual worth suing.”

Catastrophic damage?

It struck me that what put this owner into a litigious frame of mind was not really the unexpected cost of repairing his engine, but rather his conviction that the damaged crankshaft cluster gear could have gotten him hurt or killed had he not detected the problem on the ground prior to takeoff. Frankly, I didn’t believe this, and I explained the reason for my skepticism.

Any metal chipped off the cluster gear would have fallen into the oil sump. Any large pieces—larger than about 1/16”—would have been caught by the suction screen on the oil pickup tube. Smaller pieces might have made it through the suction screen and the oil pump, but would have been caught by the oil filter and not gotten any further. Only if the oil filter became clogged with thousands of metal particles would it have been possible for the oil filter bypass valve to open and permit metal to enter the oil galleries and contaminate the bearings and possibly damage the crankshaft.

I asked the owner how much metal was found in the oil filter and he replied, “very little.” This told me that the damage to the engine wasn’t anywhere near as serious as the owner had been led to believe. I suggested to check with the engine shop to find out precisely what damage had been found.

A few hours later, the owner called me back to say that he’d talked to the engine shop and obtained more information about its findings. The bottom end of the engine was indeed found to be undamaged, just as I’d predicted. Beyond the damaged cluster gear, the only damage found by the engine shop was some scoring of the oil pump housing plus some scoring of the pressure relief valve (PRV) seat, both of which are part of the accessory case on the back of the engine.

The PRV is what regulates oil pressure, and the damage to the PRV sear is what caused the low oil pressure indication that the owner observed. The effect of that damage would have been mainly at low RPMs (e.g., taxi and runup) and most likely would have been barely noticeable in flight.

The engine required a new accessory case (about $7,000) and a new cluster gear (about $3,000). The remainder of the cost would be for labor and some miscellaneous parts. The Liberty owner summed this all up succinctly: “This sucks, but it’s part of plane ownership, I guess.” My thought exactly.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: