Mechanics approve an aircraft for return to service after maintenance by signing a logbook entry, but pilots actually return the aircraft to service by flying it. Never forget that on the first flight after maintenance, you’re a test pilot…so please act accordingly.

For months, a client of mine had been searching for a Bonanza A36 to buy. He’d narrowed his search to two very promising candidates.

One of them had recently suffered a “forgot to remove the tow bar” prop strike. This necessitated an engine teardown inspection and prop overhaul, both paid for by insurance. The seller was appropriately upbeat in his communications with my client:

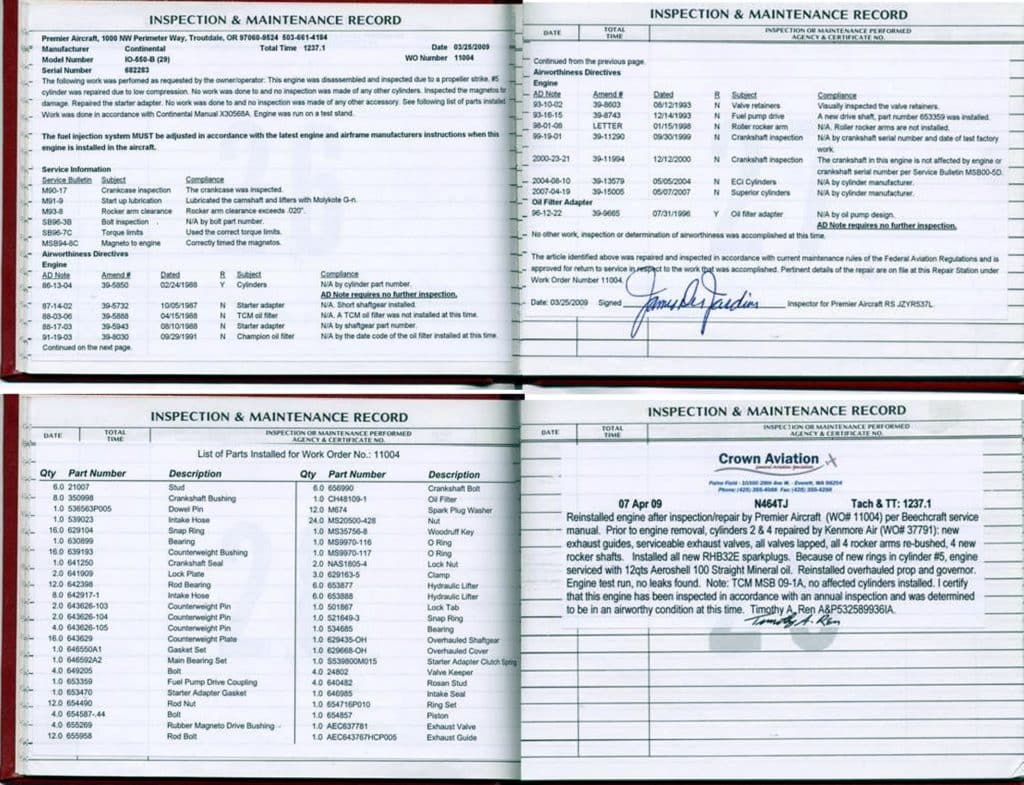

The engine in the plane was torn down and no damage that was a result of the tow bar incident was present. I’ve included the log book entries for the tear down and the final entry for the annual.

While this tow bar event has been a royal pain in the rear, we have ultimately ended up with a greatly upgraded plane and one that the buyer can have a extremely high level of understanding and confidence of the condition of the engine at 1,237 hours (like no other plane on the market). A Magnaflux procedure was completed on all steel parts of the engine (crank shaft, connecting rods, etc) which would show any microscopic cracking and a Zyglo procedure done on all the aluminum internal parts to also show any microscopic cracking.

- All internal engine AD’s were completed.

- The starter adapter was overhauled. (The shop told me this is a big deal, $1,200-$1,400 in expense and is usually only done on rebuilds.)

- All new crank shaft bearings, connecting rod bearings and some other bearings (all replaced as a normal course of teardown)

- 12 new hydraulic lifters (these were found to have excessive wear and were recommended to be replaced.)

- New three bladed prop

- Newly overhauled hub with all new hub seals

- New deice boots

- Engine completely cleaned internally (all residue and sludge deposits removed)

- Lots of new parts, pins, gaskets, bolts, etc. etc. (see parts list)

It is important to note that “NO” damage of any type was found related to the tow bar incident. As I stated above this plane is in great shape and now a completely known commodity. This plane won’t require a pre-buy, because more information than one could ever dream of getting in a pre-buy is already available.

Less than a week later, my client received this downbeat follow-up from the seller:

I wanted to let you know the Bonanza is off the market—permanently. On the test flight after the new prop, tear down, etc., the prop had an overspeed situation and the engine blew up while my partner was on the way to San Juan. No one was injured in the accident. It is kind of sad, she was such a nice aircraft!!

Accident flight

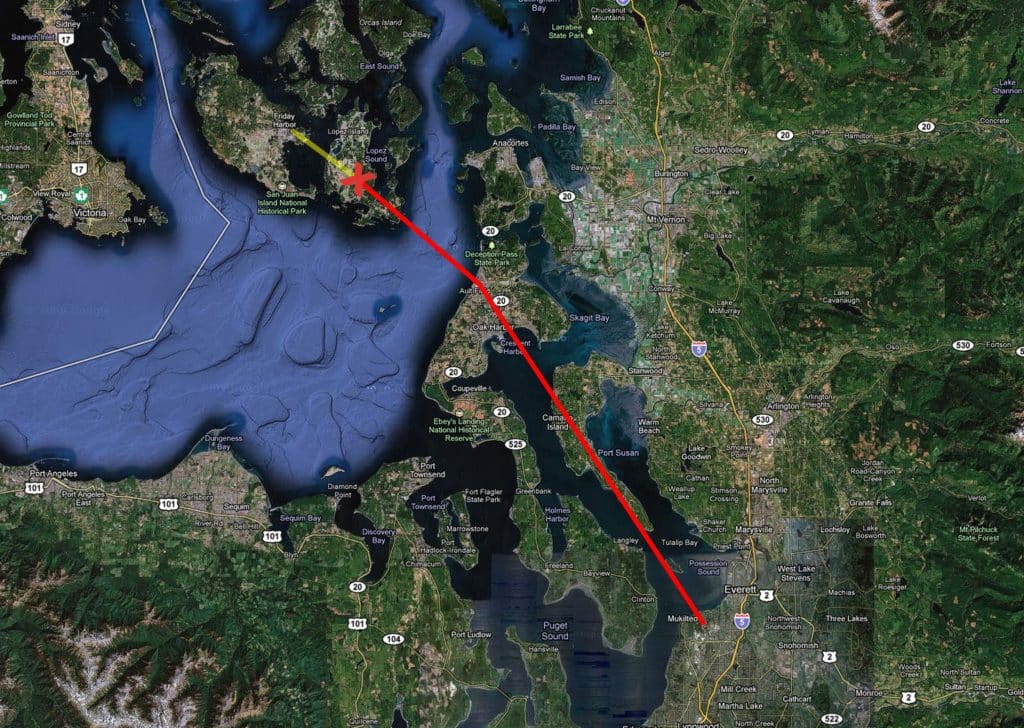

San Juan is the largest of a dozen hilly outcroppings known collectively as the San Juan Islands in the middle of the massive Puget Sound located between Seattle, Wash., and Victoria, British Columbia. San Juan Island is the site of picturesque Friday Harbor, with its active little GA airport that is a popular $100-hamburger destination.

The local newspaper—The Islands’ Weekly—carried an interesting story and some pretty dramatic photos of the crash scene on Lopez Island just east of the intended destination of San Juan Island.

According to the newspaper account and the NTSB preliminary report, the 50-year-old owner of the 1996 Bonanza A36 loaded his 43-year old girlfriend and her two young sons into the airplane and took off from Paine Field in Everett, Wash., for the 30-minutes overwater flight to Friday Harbor.

The Bonanza overflew Whidbey Island NAS airspace at 5,000 feet and began to descend overwater as the craft headed toward the San Juan Islands. Shortly thereafter, the pilot observed RPM increasing. He pulled back the prop control, but RPM continued to rise. He then throttled back in an attempt to control the propeller overspeed, but he heard a loud bang from the engine followed by smoke in the cockpit and loss of engine power.

The pilot was now over Lopez Island (east of San Juan Island) and attempted to reach a small airstrip on that island but quickly determined he couldn’t make it. He initiated a forced landing on a nearby road, had to pull up at the last minute to avoid a vehicle, then landed on the road but had the left wing strike a wooden fence post, resulting in substantial structural damage to the left wing and twisting and buckling of the empennage.

The pilot and his three passengers were treated for scrapes and bruises by the Lopez Island Fire Department, then checked into a local hotel. The Sheriff of Lopez Island was quoted by the newspaper as saying, “The aircraft’s fortunate landing was due in great part to the pilot’s composure and skill.”

What was the pilot thinking?

That may be true, but I can’t help asking myself what on earth possessed this pilot to conduct his initial post-maintenance test flight (immediately following an extensive engine teardown and propeller overhaul) on an overwater flight with a cabin full of passengers including young children? Could he possibly have been oblivious to the extremely high risk associated with such a flight? What part of “post-maintenance test flight” did he not understand?

Unfortunately, the FARs are not particularly helpful:

§ 91.407(b) No person may carry any person (other than crewmembers) in an aircraft that has been maintained, rebuilt, or altered in a manner that may have appreciably changed its flight characteristics or substantially affected its operation in flight until an appropriately rated pilot with at least a private pilot certificate flies the aircraft, makes an operational check of the maintenance performed or alteration made, and logs the flight in the aircraft records.

This regulation requires a test flight to be made (without passengers) and logged after any maintenance to the aircraft “that may have appreciably changed its flight characteristics or substantially affected its operation in flight.” But the reg leaves quite a bit to the imagination. Exactly what kind of maintenance meets this definition? Who makes the call whether or not a post-maintenance test flight (without pax) is required? The regulation doesn’t say.

I would like to think that in a perfect world, a conscientious mechanic would have counseled the owner to perform a post-maintenance test flight without passengers in the vicinity of the airport, but clearly that did not happen in the case of the accident airplane. I can find nothing in the FARs to suggest that the mechanic had any regulatory obligation to offer such counsel. Because §91.407(b) is located in Part 91 Subpart E (which speaks to owners) rather than in Part 43 (which speaks to mechanics), I think it’s pretty clear that the FAA looks to the owner, not the mechanic, to make the call.

Certain kinds of maintenance—horsepower increase, speed mod, STOL kit, etc.—obviously require a post-maintenance test flight, since these alterations are specifically intended to “appreciably change flight characteristics.” But what about an engine teardown or prop overhaul? Could these be expected to “appreciably change flight characteristics” or “substantially affect the aircraft’s operation in flight”? In a perfect world, I suppose not.

But ours is hardly a perfect world. In our real world, mechanics and technicians make mistakes—lots of them! As I’ve discussed in previous columns in EAA Sport Aviation, NTSB data clearly demonstrates the risk of a catastrophic engine failure on the first flight after a teardown or overhaul or rebuild is alarmingly high. More generally, the first flight after maintenance is by far the most likely time for an equipment failure that can compromise safety of flight.

In my view, a test flight should be made every time an aircraft is returned to service after maintenance. The test flight should be made without passengers, in day VFR conditions, and conducted in a safe environment in close proximity to an airport in case something goes wrong and the pilot needs to put the plane on the ground quickly. Arguably, the FARs don’t require this, but to my way of thinking it’s just common sense.

Not An Isolated Case

Two days after I learned about the A36 crash, I received a phone call from the owner of a 1966 Mooney M20C who wanted to put his aircraft under professional maintenance management with my company. “I feel compelled to warn you,” he told me, “that this aircraft hasn’t flown for two years.” He then proceeded to tell me the backstory.

It seems that the Mooney owner had flown his aircraft to Nassau in the Bahamas, and while in Nassau he suffered a prop strike involving some object at the airport. His aircraft went into the shop at Nassau, he contacted his insurance agent, and ultimately the underwriter issued the Nassau shop a check for $25,000 to pay for the engine teardown, prop replacement, and minor airframe repairs.

Unfortunately, receipt of this advance payment relieved the Nassau shop of any real incentive to get the Mooney repaired quickly. Much to the owner’s frustration, things progressed at a glacial pace. The shop ultimately shipped the engine to Florida for teardown, ordered a replacement prop, performed some airframe repairs, reinstalled the engine, and installed the prop. By the time the Nassau shop approved the aircraft for return to service, a full year had elapsed.

The owner took an airline flight to Nassau, hopped into his Mooney, and launched overwater for the 160 nm flight to Ft. Lauderdale. Within minutes, the owner discovered that his fuel pressure gauge was reading far below normal, his engine was unable to produce more than about 50% power, the propeller pitch was uncontrollable, and the landing gear would not fully retract. Despite all these discrepancies, the owner was apparently so desperate to get his airplane back to the U.S. mainland that he continued the flight over the high seas and miraculously managed to make it to Ft. Lauderdale, where the Mooney remained in a repair facility for the better part of another year while the multiple discrepancies were troubleshot and resolved. The Florida phase of this ordeal involved a second engine teardown, replacement of the prop governor, carburetor, fuel pump, fuel selector valve, and extensive airframe repairs.

When my firm finally took over maintenance management responsibility for this aircraft, we called the director of maintenance of the shop in Ft. Lauderdale to inquire about the condition of the aircraft. “Let me put it this way,” said the DOM, “I’m sure glad he didn’t fly over my house!” The DOM made it clear that after inspecting the Mooney, he found it quite astonishing that the owner/pilot managed to make it from Nassau to Ft. Lauderdale without winding up in the Atlantic Ocean.

Clearly, someone in high places was looking after him that day. What part of “post-maintenance test flight” didn’t he understand?

Be careful out there!

Not long ago, I received an email from another managed maintenance client, a brilliant engineer and owner of a beautiful Cirrus SR22. My firm just finished managing his annual inspection, and he was making arrangements to pick up the airplane from a Cirrus authorized service center in Southern California. He’d mentioned that he needed to pick up the airplane Friday, because on Monday he was leaving on a three-week transcontinental trip. His email asked:

Should I ask the mechanic to fly with me around the pattern for an in-flight test? I have never done this; mostly I just preflight the plane and then fly away. What are your thoughts?

What advice do you suppose I offered him?

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: