Time Between Overhaul (TBO) is a strange concept. The FAA, in its infinite wisdom, requires aircraft engine manufacturers to publish TBOs for their engines, but doesn’t require aircraft owners to abide by them. An owner is free to continue flying behind the engine as long as he or she desires, so long as the engine remains airworthy.

Yet many owners and mechanics start getting nervous and uncomfortable as they see tach time approach published TBO. Countless numbers of healthy engines are needlessly euthanized when their time-in-service approaches that consecrated number. Doing so is not an FAA requirement—it’s more like a religious belief.

Mike’s Teachable Moment

Savvy’s founder Mike Busch had a teachable moment about 30 years ago that convinced him to stop believing in overhauling at TBO. Mike had purchased a Cessna 310 twin whose two TSIO-520 engines were just 100 hours shy of Continental’s published TBO of 1,400 hours. It didn’t take long for him to get there. When he did, he asked for advice from several friends who were veteran A&P/IAs. Their advice was, “keep on flying it as long as it’s healthy.” And that’s what he did.

When the engines reached 500 hours past TBO, Mike started to get nervous, and figured he’d pushed his luck far enough. So he bit the bullet and sent the engines off to a very good overhaul facility. He asked the engine shop’s owner to give him a call when both engines had been completely torn down and measured so Mike could come visit the shop and survey the damage. He was really curious to see what the inside of those engines looked like at TBO+500. A few weeks later, the engine shop owner called to say it would be a good time to come look at the torn-down engines.

When Mike got to the engine shop, he was astonished by what he saw. The bottom end of both engines were pristine. The crankshaft and camshaft were both perfect. The main and rod bearings exhibited hardly any wear. The cylinder barrels measured within .001” of new limits, although the valve guides were a bit worn. All six cylinders were reused after re-valving and honing them.

“These engines could easily have gone another 1,000 hours without breaking a sweat,” the engine shop owner told Mike. “Whatever you’ve been doing with these engines, keep doing it.” At that moment, Mike vowed that he’d never again allow his engines to be torn down without some compelling reason.

Mike flew those engines uneventfully until they reached TBO again (1,400 SMOH) and kept going. They were still doing fine when they reached 200% of TBO (2,800 SMOH).

Finally, at about 3,300 SMOH one of the pistons in the right engine fractured and dropped a large piece of piston skirt into the oil sump. On its way there, the liberated piece of piston skirt tangled with the spinning crankshaft (and lost), arriving at the sump as a bunch of marble-sized chunks of aluminum. Interestingly, the engine didn’t stop making power or start shaking noticeably. In fact, it ran amazingly well despite its underweight and lopsided piston until Mike elected to shut it down. However, all those aluminum pellets in the oil sump convinced Mike that “it was time.” He had the right engine overhauled.

True to his vow, Mike did not overhaul the 3,300 SMOH left engine since it wasn’t contaminated and was still running fine. As a compromise, he decided to replace all six cylinders (which by now had over 5,000 hours on them) and all six pistons (which came from the same batch as the one that failed on the right engine). He also had all six connecting rods fit with new bearings and bushings. But the engine never came out of the plane and the case was never split. Five years later, that engine is still flying and showing every indication of still being happy and healthy.

Rick’s Experience

In 2001, Mike’s friend Rick bought a very early Cirrus SR22 powered by a Continental IO-550-N engine with a published TBO of 2,000 hours. When Rick’s engine started to approach that age, Mike encouraged him to keep on flying.

At 2,190 hours, during an annual inspection, Rick’s A&P reported that two of the six cylinders had tiny cracks developing between the top spark plug hole and the fuel nozzle.

Cracks in this location are very common with these cylinders, and are not particularly consequential—they never have caused any sort of catastrophic cylinder failure—so we would be inclined just keep an eye on them to make sure they don’t grow larger or exhibit signs of fuel seepage, but Rick’s A&P felt the two cylinders needed to be replaced.

At this point, Rick did something quite radical—something we tried but failed to persuade him not to do. He had his A&P remove the engine from the airplane, crate it up, and ship it lock, stock and barrel to a very good engine overhaul shop in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Rick instructed the engine shop to remove all six cylinders, inspect the cam and other bottom-end components visible with the cylinders removed, and advise Rick what needed to be done.

At the time, we told Rick that we thought this was a gross overreaction to a trivial inspection finding. In hindsight, it was probably indicative of Rick’s nervousness about going over TBO. Continental had poured a cup of TBO-laced Kool-Aid, and Rick had apparently taken a sip.

The engine shop did as instructed, and advised Rick that the cylinder head cracks were not really cracks, just minor cosmetic flaws in the head castings that could be polished out easily. The cylinders had very little wear, and the bottom-end components looked great. The pistons were a bit dirty and a couple of the oil control rings were fouled with lead sludge, but otherwise there was really nothing wrong with the engine. The shop cleaned and re-ringed the pistons, honed and re-valved the cylinders, put the engine back together, and shipped it back to Rick’s A&P.

This was Rick’s teachable moment. He took the vow.

When your engine talks, listen up!

Fast forward about a decade…

Rick took his SR22 on its annual pilgrimage from Southern California to Oshkosh, Wisconsin for AirVenture week. After AirVenture, he continued up to Canada before heading back home. During this extended cross-country trip, Rick had the vague sense that the engine wasn’t running quite as smoothly as usual. So he decided to make a stop just northeast of Minneapolis at a shop that is well-known in the Cirrus community for its ability to do powerplant vibration analysis.

To rule out the ignition system as the source of the perceived roughness, the A&P owner of that shop sent both magnetos out for overhaul and replaced all twelve spark plugs. While waiting for the mags to come back, he changed the oil and cut open the oil filter for inspection. The filter media contained a small quantity of metallic flakes.

The flakes were non-magnetic and had a yellowish appearance. The quantity of metal wasn’t particularly alarming. But the engine had now accumulated more than 3,500 hours and didn’t seem to be running quite as smooth as usual. Rick had a visceral sense that the engine was trying to talk to him, and decided he’d better listen carefully.

Upon Savvy’s recommendation, Rick sent out an oil sample and the filter media for laboratory analysis. The oil analysis report came back with no elevated wear metals. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) report for the filter media stated:

“A TRACE AMOUNT OF BRONZE FLAKES WERE REMOVED FROM THE FILTER ELEMENT, CLOSEST MATCH AMS 4842, RANGING IN SIZE FROM 788 X 455 TO 546 X 448 MICRONS.”

Aerospace Material Specification (AMS) 4842 is a leaded bronze alloy composed of copper, tin and lead. Savvy looked it up and advised Rick that its most common use was for “bearings for high speed and heavy loading, pumps, impellers and corrosion resistant applications.” Key features of this bronze alloy are: “Will tolerate moderate loading, moderate to high velocity impact loading or pounding. Needs adequate lubrication but tolerant of boundary conditions and inaccuracies of fit.”

We advised Rick that the flakes were almost certainly bearing material from the engine’s main bearings, connecting rod bearings, or both. Rick concluded that the engine was telling him, “it’s time.” So, instead of heading home to California, Rick wisely decided to fly the airplane to Tulsa and put it in the capable hands of his trusted engine shop.

What Rick’s teardown revealed

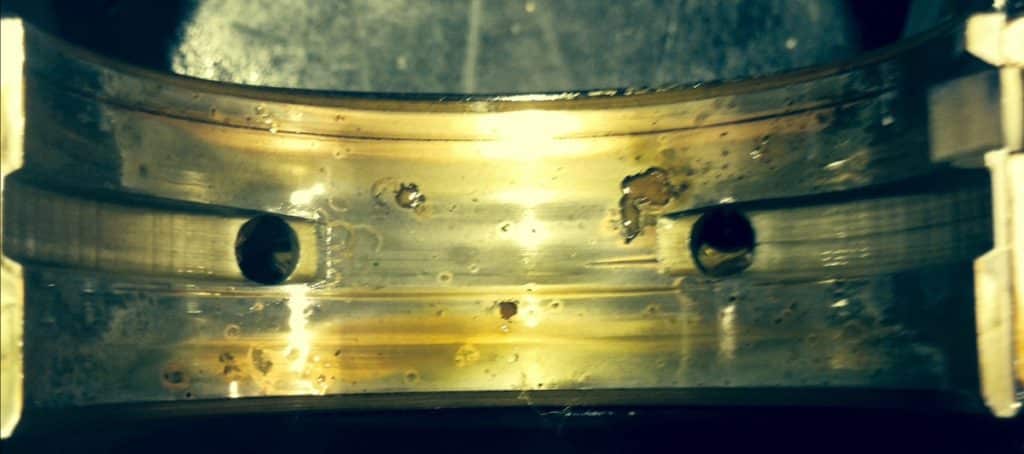

The engine shop pulled Rick’s engine and commenced to tear it down. Once the case was split, the source of the bronze flakes in the oil filter became obvious—one half of the #2 main bearing exhibited serious spalling.

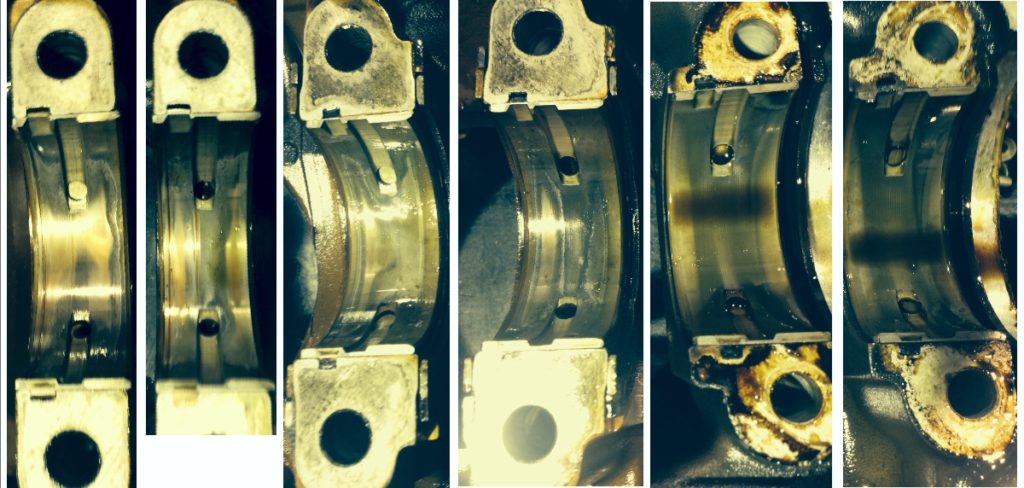

In fact, so much of the bearing’s leaded bronze layer had flaked off (compared to the small amount in the oil filter media) that it was apparent that this deterioration had been going on undetected for quite some time. Interestingly enough, the opposing half of the #2 main bearing was in much better shape:

The remaining main bearings (#3, #4 and #5) were still in excellent condition:

The engine shop cut open the oil filter again, and found very little metal.

Rick had been doing regular oil analysis on the engine, and asked why the oil analysis reports had never shown any elevated levels of bearing elements like copper or tin. We explained that this was simply because the oil filter had been doing its job. Since the flakes that were coming off the bearing were much larger than the 50-micron rating of the filter media, all of the metal was caught by the filter and none remained in the oil that was drained into the sample jars he sent to the lab.

It was not clear why just one of the #2 main bearing shells had started coming apart, while its opposite number and all the other main bearings remained in good condition. Rick suggested that one thing that might conceivably have precipitated it was that the plane had undergone some major structural composite repairs that kept it grounded for many months, and the shop performing those repairs had done nothing to protect the engine from corrosive attack. Perhaps if the engine had been “pickled” during that extended period of downtime, Rick’s engine might have made it to 4,000 SMOH.

While the reason remains a mystery, one thing is clear: The engine was talking and Rick was listening.

Savvy has saved its SavvyMx managed maintenance clients millions of dollars by helping them say “no” to unnecessary maintenance. For example, we try hard to provide our SavvyMx clients with both the knowledge and the courage to continue to fly their engines until the engine itself tells them when the time has come for an overhaul. Using technologies like borescopy, SEM, and engine monitor data analysis, when their engines start to speak, we help our clients listen and interpret what they’re saying.

In Rick’s case, the total cost of the overhaul—including removal, reinstallation, new shock mounts and hoses, etc.—came to about $45,000. Dividing this by the 2,000-hour TBO yields a reserve for overhaul of $22.50 per hour. Thus, by deferring the overhaul for 1,500 hours past TBO, Rick earned a windfall of $33,750.

Rick’s subscription to SavvyMx cost him $750 per year. So the windfall he received by appropriately deferring his engine overhaul was enough to pay for SavvyMx for the next 45 years. Or to purchase roughly 7,000 gallons of 100LL, enough for him to fly to Oshkosh and back for the next 20 years.

While we can’t guarantee every SavvyMx client a $33,750 windfall like Rick’s, we can say that Savvy invariably saves its clients more in reduced maintenance cost than what we charge them in annual subscription fees—often a great deal more.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: