Before you approve any costly or invasive repair to your aircraft, make sure the discrepancy is real.

Arguably the worst part of being an aircraft owner is the annual ordeal of putting your plane in the shop every 12 calendar months and then bracing yourself for bad news. Over the past 4 years, my company has managed more than 700 annual inspections and more than 6,000 lesser maintenance events, so it’s a safe guess that we’ve dealt with tens of thousands of mechanical discrepancies. Sometimes the bad news is painful and costly to the aircraft owner. But surprisingly often, it turns out to be nothing more than a false alarm.

A couple of months ago, for example, a client’s single-engine airplane went into a big, well-known Florida service center for its annual ordeal. Within hours, the shop reported that cylinder #3 measured 38/80 on the compression test, with air audible at the exhaust tailpipe. (This was a Continental engine, and the master orifice no-go limit was 46/80.) The mechanic attempted to “stake” the #3 exhaust valve but was unable to improve the reading. The shop said the #3 cylinder needed to be removed and sent to a cylinder shop to be re-valved and honed, and then reinstalled with a new set of piston rings. The estimated cost of this work was quoted at $2,200.

We checked the airplane’s downloaded digital engine monitor data and found that the #3 EGT appeared normal, with no hint of the slow, rhythmic oscillations characteristic of a burned exhaust valve. We asked the shop to inspect the #3 exhaust valve with a borescope, and they reported back that the inspection results were “inconclusive.” Further questioning revealed that the exhaust valve had a symmetrical appearance under the borescope (see Fig. 1), with none of the lopsided, green-tinged appearance characteristic of a leaking exhaust valve.

At this point, we asked the shop to complete the annual inspection, and indicated that we would arrange to have the owner fly the airplane for at least 45 minutes and have the #3 compression rechecked, as directed by Continental Service Bulletin SB03-3. The shop’s director of maintenance sounded less than thrilled with this idea, asking “How do you propose we sign off the annual on an aircraft that has a cylinder that measures 38/80, less than the minimum required compression?”

We suggested the following wording in his logbook entry: “Borescope inspection of cylinder #3 and digital engine monitor data analysis revealed no abnormalities. In accordance with Continental SB03-3, the aircraft will be flown for a minimum of 45 minutes and cylinder #3 compression will be re-tested; cylinder is not determined to be unairworthy at this time.” The director of maintenance somewhat reluctantly agreed to this.

At the completion of the annual, we asked the owner to fly the airplane for an hour and then bring it back to the shop. We asked the shop to remove the top cowling and repeat the compression test of the #3 cylinder only, and do so as quickly as possible so that the cylinder could be tested as hot as possible. The result of the re-test was 72/80 (!) and the happy owner was able to spend that $2,200 on avgas instead of maintenance.

(In previous columns, I’ve discussed my distrust of compression tests, and suggested that borescopy and digital engine monitor data analysis are much more reliable indicators of cylinder condition. This is a good example of why I feel that way.)

Suspected Head Crack

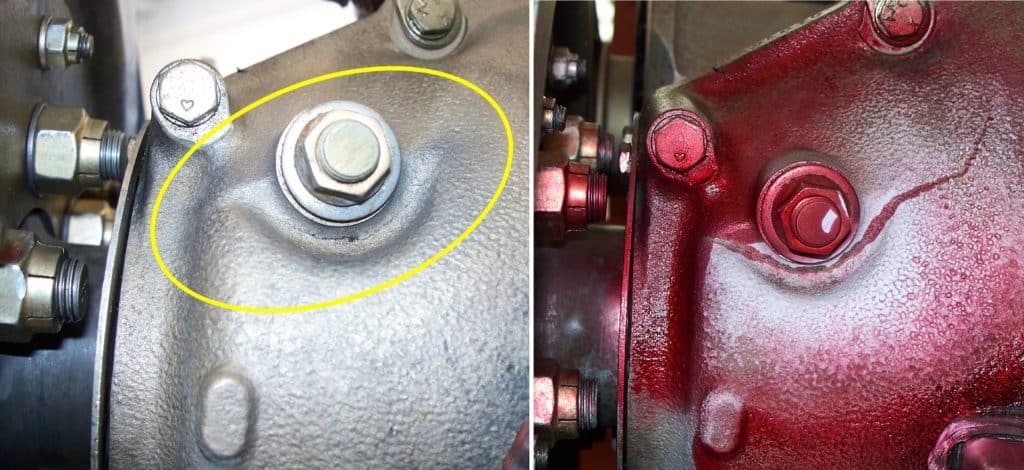

The same week, another client’s airplane was undergoing an annual inspection at another shop. The inspecting IA reported that he found a cracked cylinder head. He sent us a pretty convincing digital photo (see Fig. 2, left image) that showed what appeared to be a crack between the top spark plug hole and the fuel injector nozzle boss. The shop recommended replacing the cylinder, and quoted $3,000 for a new cylinder plus removal and installation labor.

This is the “standard” location for cylinder head cracks to appear on Continental engines. In fact, I’ve lost two cylinders to head cracks in this exact location on my own Continental-powered Cessna 310. On the other hand, our experience is that more than half of the reported cracks in this area turn out not to be cracks at all, but rather superficial cosmetic flaws in the head casting. In fact, unless the crack is clearly blue-stained and leaking fuel, it rarely turns out to be an actual crack.

Therefore, in accordance with our standard operating procedure, we asked the shop to sand the suspected crack area smooth and then perform a dye penetrant inspection (DPI) of the area. DPI is a quick, low-cost inspection method used to locate surface defects on non-ferrous metals. The DPI kit contains three aerosol cans—cleaner, penetrant, and developer—and the inspection procedure is simple:

- Spray the surface with aerosol cleaner, and they wipe dry.

- Spray the surface with aerosol penetrant (typically deep red in color), and allow it to soak into any surface flaws for 10 to 30 minutes.

- Wipe the surface with a clean cloth moistened with aerosol cleaner to remove all residual red-dyed penetrant from the surface.

- Spray the surface with aerosol developer powder, and allow to dry to an even white powdery layer.

- Inspect the developer-covered surface. Any cracks will show up clearly as a red line on the white surface, as red-dyed penetrant embedded in the cracks is wicked up out of the crack and absorbed by the white powdery developer.

The shop performed the DPI procedure and sent us a photo of the results. (See Fig. 2, right image.) The test showed clearly that there was no crack in the cylinder head, and that what appeared to be a crack was a superficial cosmetic flaw. The cylinder remained in service, and the owner found a better use for his $3,000.

A few weeks later, a friend of mine (but not a managed maintenance client) called to tell me that his shop had just replaced a cylinder on his engine due to the presence of a similar crack. I asked whether the shop had performed a DPI to verify the crack before yanking the jug. My friend said he’d requested that, but the IA demurred, claiming it would be a waste of time and adding “I know a head crack when I see one.” At my urging, my friend retrieved the removed cylinder from the shop and performed his own DPI. No crack! He took the jug to the shop owner, who sent it out for more sensitive eddy-current inspection. No crack! The shop owner was embarrassed, and issued my friend a several thousand dollar refund to cover the cost of the new cylinder plus the removal and installation labor.

Suspected Crankcase Crack

Yet another client had been complaining of an oil leak near the front of his Continental IO-360 engine. He kept cleaning off the oil with solvent, but it kept reappearing. During his annual inspection last week, the shop said they thought the oil was coming from a crankcase crack. That would have been the ultimate sort of bad news, because it would have necessitated sending the engine out for a teardown and crankcase repair—potentially a $16,000 event.

We asked the shop to clean and sand the area and perform a DPI. No crack was found. The shop even tried pressurizing the crankcase with shop air, heating up the suspected area with a torch, and spraying it down with soapy water. Still no evidence of a crack. Ultimately, the shop concluded that the oil was actually coming from a bad propeller governor gasket. Whew!

This owner lucked out. We’ve seen a rash of crankcase nose cracks in Continental IO-360 engines. Figure 3 shows the crankcase of another client who wasn’t so lucky. Note how the crack is quite subtle and would have been easy to miss, but the DPI makes it really obvious.

Unfortunately there’s no magic vaccine that provides immunity from bad news at annual inspection time. Stuff happens. But things aren’t always what they seem. You can often save yourself thousands of dollars (and sometimes tens of thousands) by insisting upon conclusive verification of a discrepancy before you approve costly and invasive work such as cylinder removal or engine teardown. Proper maintenance is important, but unnecessary maintenance is a travesty—and it happens far more often than you might think.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: