I have been flying my Bellanca Viking for 29 years now. I have had two unexplained events – one electrical and one combustion – both in day VMC. I was alone for both. The electrical event was on approach to a central California airport with a tower. I had deployed the first notch of flaps and the gear was down and showing 3 greens. I had contacted the tower but had not yet received landing clearance. Suddenly the whole radio stack and the nav gear went dark and quiet. A few seconds later, as I was refreshing my memory on light signals, everything came back on. I advised the tower that I was having an electrical problem and planned to continue my approach and land, but that I might go silent again. Power stayed on for approach, landing, and my taxi to parking. The next day I investigated by powering up each radio – one at a time – then the whole stack. Nothing happened that day, or in the many flights since.

The combustion issue was on an IFR flight in VMC from Santa Barbara to Palomar just north of San Diego. It was a very windy Spring day and on that leg I was flying into about a 30 knot wind, with at least steady chop and occasional up and down drafts as I passed Camarillo on the way to the Fillmore VOR at 9000. I was on the left tank when the engine lost power. In those 29 years I have run the aux tank dry three times. My SOP used to be to put my hand on the fuel selector when the aux tank got low, to remind me to switch. In all three cases I got distracted by something else, like changing a frequency or the heading bug and my hand came off the selector until the fuel ran out. Good on you if you’ve never done this – I have talked to a lot of pilots who have. Now my SOP is to switch aux to left or right before it gets so low. The hand doesn’t loiter on the selector – I decide to switch and make the switch.

On this day my hand wasn’t on the selector, I was busy flying in rough air. When I heard that familiar sound of sudden quiet my hand got to the selector pretty fast, I switched from left to right and hit the boost pump, and the engine came back to life. All the gauges looked normal, so rather than cancel IFR and divert to Camarillo I pressed on. I wasn’t thrilled about flying over the crowded LA airspace with an engine problem, and resolved that if anything looked or felt wrong I would divert right away. Then ATC gave me a heading change and a climb to 11000. The heading change took me away from the hills and the air got smoother as I climbed. I was still spring-loaded for a change of plans if anything got hinky – it never did and I stayed on the right tank all the way to landing. On the ground, I went back to the left tank for taxi with no problems. The next day I investigated for water or debris in the left tank, or a blockage of the induction system and did a couple of runups on the left tank – all without incident. My theory is that it wasn’t a fuel problem – it was because of the unstable air I was flying through.

An anomaly that can’t be replicated is maddening, whether it’s your airplane, or your car or your computer. Sometimes clients will get a file parse error uploading a file, so we look at the file, and if it looks intact we try and upload it, and often it works. Mike wrote an article called Where’s the Smoking Gun about the desire to find a fouled plug or a bad mag or some tangible evidence that was the cause for an unpleasant or unexpected event. Engine data monitors have made a big difference in our ability to examine short-lived and intermittent events. But sometimes having that data shows us that something happened, and didn’t happen before or since, and can’t be replicated on the ground. With that in mind, let’s see what this month’s data reveals.

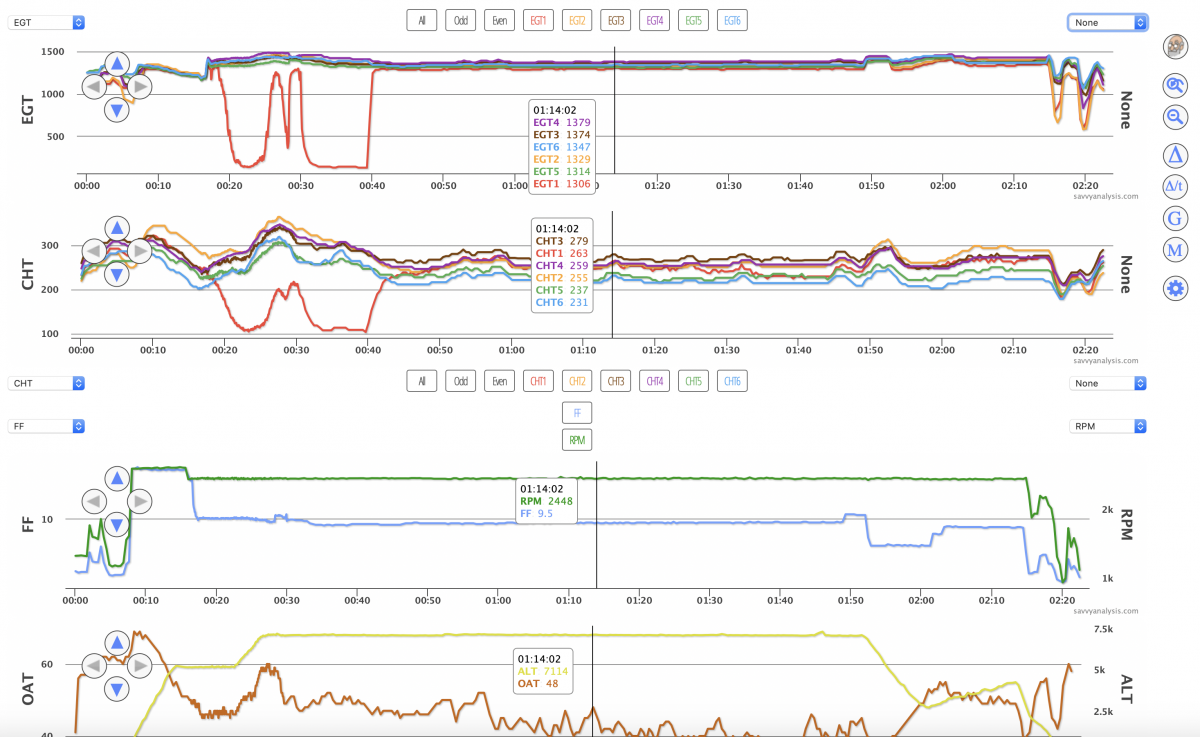

First up is data from a Cessna 172 with a Continental IO-360 and data from a JPI 730 using a 2 sec sample rate. EGT on top, then CHT, then FF and RPM, then OAT and ALT. The cursor isn’t marking anything notable – just out of the way of the big event.

If you peek between the arrows you can see that EGT and CHT 2 are a little low before takeoff. At takeoff and in climb, CHT 2 pulls away and EGT 2 is highest but just barely. Let’s stick with cyl 2 for a moment – it’s high in climb than again around the 2 hr mark for approach. Since it’s high when airspeed is low this looks like a cooling issue, not a fuel issue. But that wasn’t the subject of the ticket. Neither was the giant dip in EGT and CHT 1. The client had noticed that EGT 4 was higher than usual and asked us to take a look. That right there was a clue.

I worked this ticket and wrote back that EGT 4 was a little high, so he should probably perform a LOP mag check at his convenience. And by the way, did you notice that the data shows that cyl 1 dropped offline for about 20 minutes during your first level-off, the subsequent climb and initial cruise? Ok, technically it made two recoveries to almost normal, but both failed. If you only look at EGT and CHT, you’d wonder why this flight continued for another 90+ minutes. But when you include FF and RPM, it looks like the engine was making power the whole time. There is a little FF blip around 28 mins which looks like fine-tuning the cruise setting. Oil pressure isn’t depicted but basically it’s flat through here, too – no roller coaster.

You may have noticed the OAT drops in the climb until the first level-off, then rises as the climb resumes. That went into my thinking, too. Maybe he flew through a cloud deck or maybe even some rain, then broke out into warmer air above. Could that have caused cyl 1 to flame out?

It turns out that nothing really happened. The client reported a little bit of roughness in initial cruise that he attributed to EGT 4 being a little high. He didn’t push NEAREST on the GPS because despite an attention-getting display in EGT – corroborated by its CHT – cyl 1 didn’t fail.

We want our engine data monitors to cry “Wolf!” when there’s really a wolf, but if they cry when there’s no wolf, they just add stress to the pilot workload.

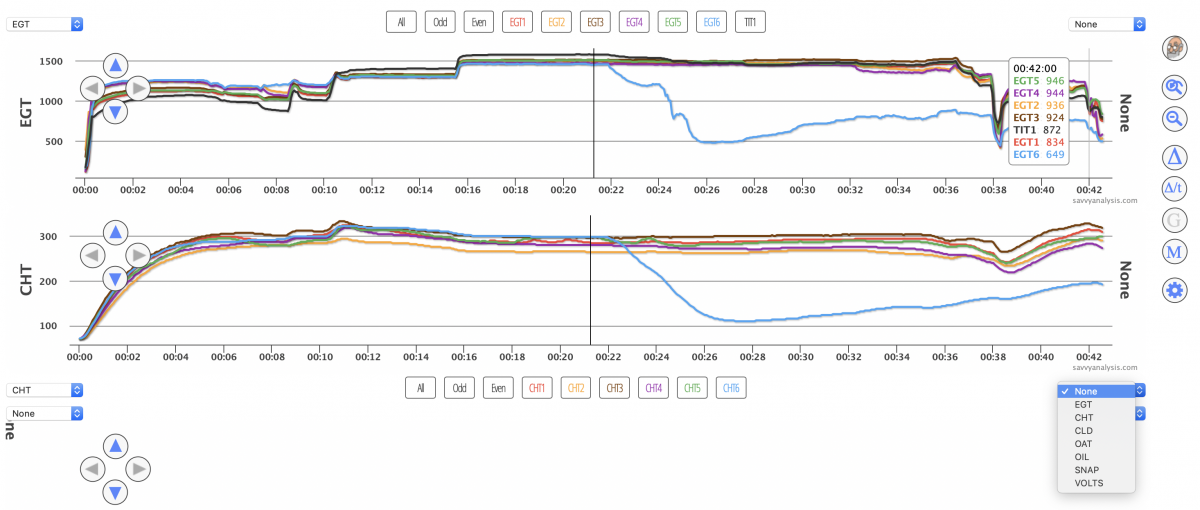

Next up is a Mooney M20K with a Continental TSIO-360 and data from a JPI 700 with a 2 sec sample rate. EGT on top, CHTs below. FF isn’t logged.

Paul Kortopates is our Mooney specialist and worked this ticket. Our client made a precautionary landing and submitted the data, and reported a moderate oil leak around the cyl 6 exhaust riser. Paul worked the ticket the next day, and by then investigation revealed failure of the exhaust side rocker shaft hold-down bolt, which led to a hole in the rocker cover and the oil leak. Fortunately all parts were accounted for in the rocker cover – teardown bullet dodged.

It wouldn’t have been fair to give you this data and ask you why cyl 6 stopped making power and expect you to come up with a sheared hold-down bolt. So here’s the puzzler. When our client landed and taxied in the engine ran rougher than it had in the air, and when he pulled the mixture to cut-off the engine kept running. After about a minute, our client turned off the engine with the ignition switch. Thoughts?

Knowing what the investigation revealed, Paul’s theory is that after the rocker shaft partially detached from the exhaust side of cyl 6, it was no longer breathing normally and exhaust wasn’t venting much air out of the cylinder – which in turn would limit the normal amount of vacuum the intake valve would see when opened. So probably a good amount of the fuel being pumped through injector 6 began pooling there and was being vented to the other cylinders through the induction manifold. In fact with the exhaust valve blocked, the venting might have been under some pressure. Extra gas courtesy of cyl 6 could have allowed the other cylinders to run on for awhile after the mixture was pulled to idle cutoff.

When you consider all the things that could have happened once that rocker got loose, this was a pretty good outcome.

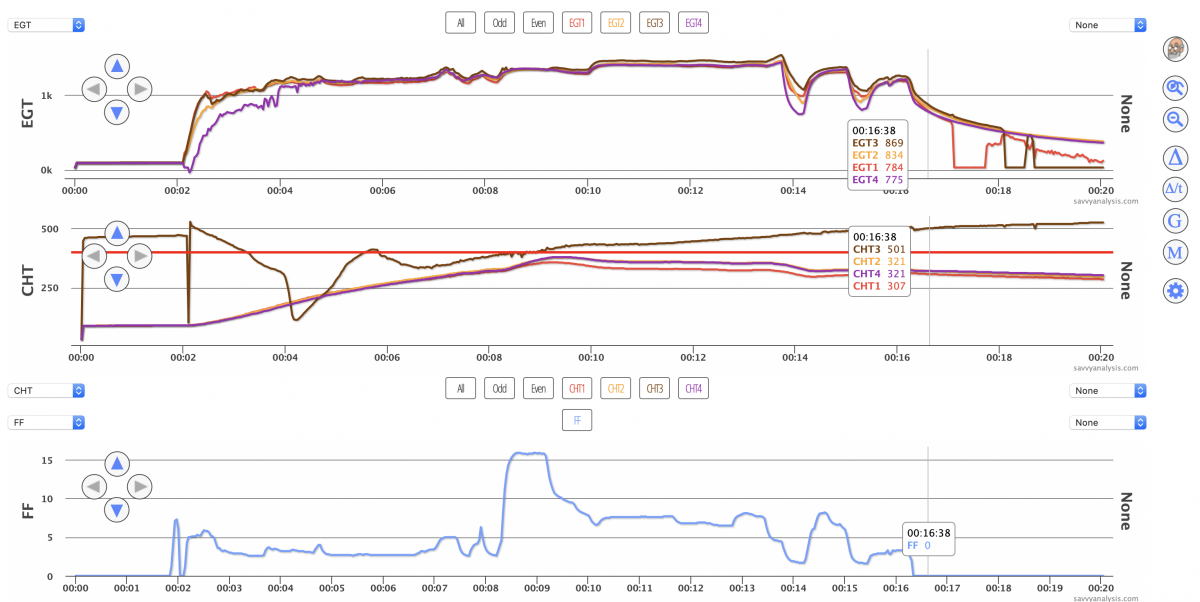

Next up is an RV-7 with a Superior IO-360 and data from a Dynon Skyview using a 1 sec sample rate. EGT on top, CHT below and FF below that.

Fortunately the Dynon powers on about two mins before engine start. It’s fortunate because with FF at zero and everything else at ambient temp, CHT 3 jumping immediately to the 470º range is yelling “Bull****” louder than Penn & Teller – on second thought make that Penn. Teller doesn’t talk.

At engine start CHT 3 drops for a second like it’s going to behave, then jumps again – which we know metal can’t do – and then appears to cool as the others warm. From this data we can’t tell if cyl 3 is healthy or running hot or cool or even making power. It has a mind of its own. Maybe most interesting is that CHT 3 continues to climb after the engine shuts down at the 16 min mark. It gets all the way to 525º F. But it might as well be 525º C for all the good it does.

In other news, EGTs 2 and 4 are a little slow to warm but are normal by takeoff. EGTs 1 and 3 have a different cooling pattern than 2 and 4 – it’s after the engine is off so let’s not spend too much time worrying about it – other than to file it away in case those EGTs look funny later on.

Feel free to post your comments about this article, or your experience with events you couldn’t replicate, and how they influenced your planning on subsequent flights.